Introduction

Jacob Lawrence (1917–2000)

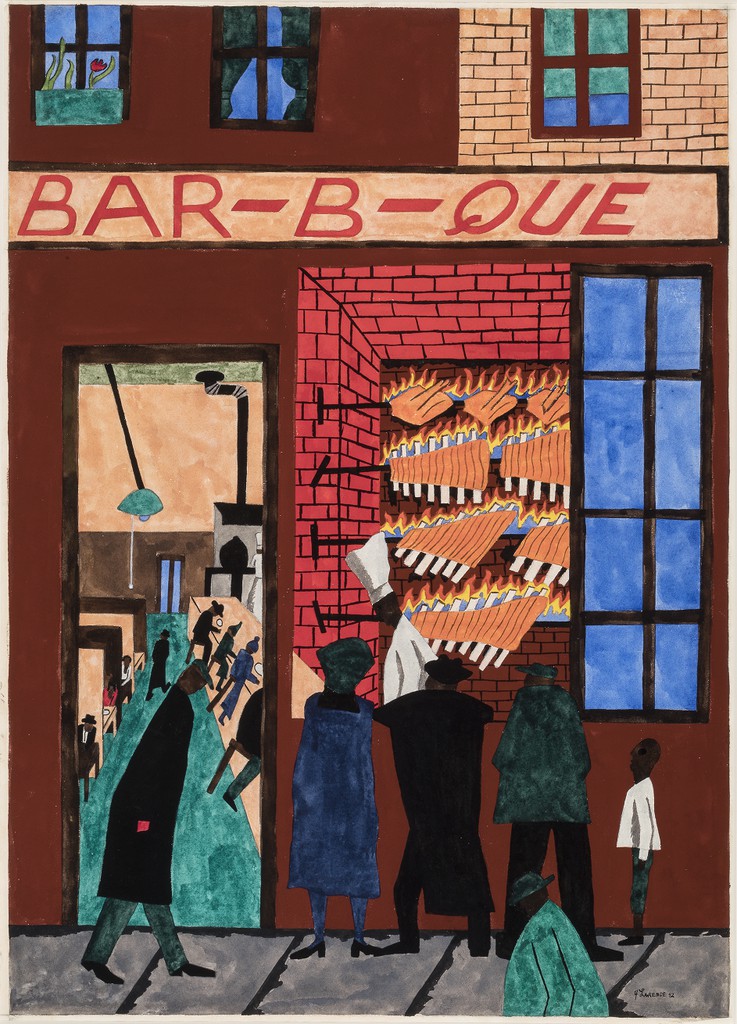

Bar-b-que, 1942

The painter Jacob Lawrence is best known for his candid and expressive portrayals of twentieth-century African American life. Bar-b-que belongs to a group of strikingly modernist works set in Harlem that he made during a time when this large African American New York City neighborhood was renowned for its cultural vibrancy. The watercolor depicts a barbecue restaurant filled with customers. A white-hatted cook prepares flaming slabs of pork ribs and roasted chickens in a street-facing kitchen as several adults and a child stand transfixed at the window. Bar-b-que features a kind of eatery common in the black South transplanted to New York City—just one reflection of the Great Migration, when from roughly 1916 to 1970, some 6 million African Americans, including Lawrence’s own family, left their rural Southern homes for cities in the North, Midwest, and West.

Learn more about this watercolor on the Terra Foundation website.

Perspective

Renowned modernist Jacob Lawrence (1917–2000) spent six decades chronicling the African American struggle for economic justice and political freedom. In the Depression-era art workshops of Harlem, Lawrence worked with brown paper and color, learning to see patterned resemblances in the world around him. He developed a lifelong attachment to tempera paint and aqueous media, and a pictorial language that articulated the blunt emotional and physical realities of working-class life in the city’s streets and tenements. The visual potency of Lawrence’s compositions was matched by his power to synthesize and portray broad historical and economic trends. Given their bold figure-ground relationships, his subjects are usually immediately recognizable. Plumbing his content, however, is like solving a puzzle by discerning relationships between word, shape, and color.

Bar-b-que is one of thirty Harlem subjects Lawrence painted in 1942–43, including rent strikes, stairwells, toilets, schoolrooms, libraries, subway commuters, rooftops, bars and bootleg whiskey, free clinics, and pool rooms. Many bear concise captions that read like excerpts from the official publications of the New York City Housing Authority. In Bar-b-que, passersby dressed in Sunday finery stop on the sidewalk to look at a tall display of ribs and chickens turning on spits in an open window; through a narrow door we see the restaurant’s full booths and bar stools—a vision of plenty and relaxation.

The carmine tiles of the rotisserie oven match the sizzling red letters on the restaurant sign spelling out the painting’s title. Given its prominence, one may assume that the word is important, and, as with other juxtapositions of word and image in Lawrence’s narratives, the subject of temporal elision or culturally specific encoding. The term “barbecue,” for example, may derive from the Haitian Creole “barbacoa”— meat prepared over a framework of sticks; such open-flame cooking was practiced in West Africa by the ancestors of American slaves, and later became a frequent part of outdoor “Juneteenth” events celebrating the abolition of slavery in the rural South.

Like the lives of African Americans moving north to escape Jim Crow laws, this laden food culture has been reframed vertically in an urban, multistory brick structure with a storefront and upstairs apartments. The rhythmic cadences of the doorway and windows, articulated in high-keyed greens and blues that may suggest longed-for foliage and sky, provide relief to the relentless red-brown grid of the built environment. A pastoral green restaurant floor leads from the sidewalk, past the black clientele, and into a kitchen in which we can see a black chef, who may well be the proprietor.