John Lewis Krimmel (1786-1821)

The Blind Fiddler, 1812

How and why did it catch on?

Wilkie’s painting depicts a cottage interior, where an itinerant musician has stopped to play for a few pennies or perhaps something to eat. Beside him is his wife, tired and glum, holding an infant; their young son warms his hands at the glowing hearth. Gathered to enjoy the impromptu concert is the resident family, with a contemplative grandfather looking on, two little girls raptly gazing, the father snapping his fingers to amuse the baby on its happy mother’s lap, an older girl who has temporarily abandoned her spinning, a quizzical dog, and a grimacing scamp pretending to play his own fiddle with a pair of bellows and a poker. The room is sparsely furnished, yet the family clearly has enough for its needs. There is an array of foodstuffs, along with children’s toys, cooking implements, a large armoire, baskets and blankets, even a small collection of books next to the bust of a minister above the mantelpiece. Pious, industrious, and comfortable, this family casts the plight of the wandering fiddler into poignant relief.

Krimmel was faithful to Wilkie’s original as transmitted through the black-and-white engraving, though he had of necessity to improvise the colors. When he exhibited the painting in 1813 at the Pennsylvania Academy, critical response was surprisingly warm, considering that the work was, after all, only a good copy of another more famous painter’s production. What roused critical enthusiasm was the recognition of a model for a truly American art capable of expressing national identity at a time in the formative years of the young republic when what it meant to be “American” was a question that had no clear answer.1 As one writer put it at the time: “The subject is one of these that daily occur in the simple walks of common life; it is delineated with truth and elegance, and exhibits without affectation, the comforts and happiness of domestic life…. [Wilkie’s] pictures are equally interesting to the learned and ignorant—they are faithful, chaste, and dignified representations of nature, conveying at the same time pleasure and instruction…. We believe his school of painting well fitted for our republican manners and habits, and more likely than any other to be appreciated at present.”2

In appropriating Wilkie’s subject and format, Krimmel played a key role in formulating an attractive and accessible model for representing purportedly authentic, everyday Americans as rural, domestic, naturally good, and happy with their lot. Further staking his claim to represent the real America, Krimmel exhibited his own Quilting Frolic (1813, Winterthur Museum, Garden and Library, Delaware) along with his copy of The Blind Fiddler at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts in 1813. A far livelier scene, it takes place in a similar, if somewhat more affluent, interior, where George Washington’s portrait has replaced the minister’s bust, and the fiddler is now black. Here, women tend to the domestic work or flirt innocently with young men, children act up, and the black fiddler, barely through the door, clearly knows his liminal place in white society.

If it struck any viewers as ironic that the Scotsman Wilkie’s vision of peasant life provided the scaffolding for the German-born Krimmel’s celebration of American country customs—especially during the ongoing War of 1812 against the British—no record of such reactions survives. Nor did it seem to concern any viewers that Krimmel (like Wilkie) liberally sugarcoated his visions of “republican manners and habits.” Thus sweetened, such compositions worked to assuage contemporary anxieties that circled around the potential of unchecked social mobility and the rise of cities to empower the disorderly and potentially dangerous masses. In the country of Krimmel’s imagination, change came slowly, if at all, for its inhabitants, who had attained comfortable “middling” status but desired nothing higher.3

The Wilkie/Krimmel template became a standard for rural genre scenes for the remaining decades of the antebellum era, when reassuringly peaceful, entertainingly moralistic, and often humorous visions of static American country life belied the turbulent realities of social change, political peril, and national expansion under the banner of Manifest Destiny.4 In the work of Krimmel’s heirs, notably William Sidney Mount (1807–1868), Francis William Edmonds (1806–1863), and Eastman Johnson (1824–1906), national identity remained firmly rooted in the American northeast.5 If their paintings referred to contemporary conflicts, it was often in an oblique or coded fashion that left room for varying interpretations. This was very much the case with Johnson’s Negro Life at the South (1859, New-York Historical Society), which was exhibited to great acclaim at the National Academy of Design in 1859, two years before the outbreak of the American Civil War. Representing a multigenerational group of slaves going about their activities in the backyard of a tumble-down house, Negro Life allowed abolitionists to deplore the wretched conditions of bondage while enabling pro-slavery advocates to see the slaves as content with their lot. One critic, however, made a surprising comparison: “The picture of ‘Negro Life at the South’ ranks with Wilkie’s ‘Blind Fiddler,’ and is a kind of Art that will be always popular, so long as lowly life exists to excite and to reveal the play of human sympathy.”6

Born in the small village of Lovell, Maine, Johnson performed a reverse of Krimmel’s transatlantic career trajectory, training in Düsseldorf, Germany, as well as in The Hague and Paris. Equipped with sophisticated technical skills, he established himself in New York in 1859, and during the Civil War (1861–65) produced a succession of politically charged scenes depicting slaves in their struggle for freedom.7 Soon after the end of the war, in 1866, Johnson—who was well acquainted with the conventions of British genre painting—revived the Wilkie/Krimmel template and put it to fresh use in two versions of a painting titled Fiddling His Way. In the Terra Foundation’s painting (Fig. 2), we see a dim cottage interior, where an older, bearded man plays for a family group: mother, baby, pipe-smoking father, three boys, and an older daughter with a broom. Everyone listens as if enchanted; only the baby breaks the spell as it squirms and reaches out toward the musician.

Eastman Johnson (1824–1906)

Fiddling His Way, c. 1866

In the other version (Fig. 3), larger and more fully elaborated, there are additional figures, a more detailed inventory of the furnishings—plain and rustic—and a decided switch: the fiddler is a young black man, neatly dressed and very serious.8 The fiddler’s race changes everything, including the implications of the title. The young man is on his “way”—but to where?

Eastman Johnson (1824-1906) Fiddling His Way, 1866 Oil on canvas, 24 1/4 x 36 1/2 in. (61.6 x 92.7 cm). The Chrsyler Museum of Art, Norfolk, Virginia, Bequest of Walter P. Chrysler, Jr., 89.60

Seated near a door, he (like Krimmel’s black fiddler in Quilting Frolic) is clearly on the edge. It is telling, too, that a trapdoor lies at his feet—perhaps an allusion to the Underground Railroad that aided (and hid) escaped slaves on their way to freedom in the North. In 1866 this young man is on the move, but unlike the desperate fugitives of the antebellum decades, he is free. Yet he is a vagabond without a home. What, the painting asks, is now his place (and that of all freed slaves); where does he belong? Is he on his way to a brighter future, or, at a time of postwar political turmoil and conflict, to a dead end?9 The question remains unanswerable, but Johnson had by then come to his own dead end with the black American’s dilemma. After 1866, he turned to the nostalgic, rustic New England scenes that would bring him renown in the 1870s.10 While the “black” version of the painting points the way to an uncertain outcome, the “white” version looks back to a vanished idyll of peace and harmony.

Only a year or two later, Lilly Martin Spencer (1822–1902) painted Home of the Red, White, and Blue (Fig. 4), which like Johnson’s painting (but with a different set of questions) is a reflection on the unsettled postwar social landscape. Born in England but raised and trained in Ohio, Spencer moved to New York in 1848 in order to advance her career. A rarity in a heavily male-dominated field, she was the family breadwinner, specializing in comic and sentimental images of the domestic realm and its inhabitants: mothers, children, servants. In Home of the Red, White, and Blue, however, the women are not darning socks or baking pies.

Lilly Martin Spencer (1822–1902)

The Home of the Red, White, and Blue, c. 1867–68

In the center of Spencer’s busy composition stands a mother (a self-portrait) in lacy white flanked by her two daughters, the elder in rosy red, the younger in rich blue. The three form a strong, brilliantly lit triangle. Behind them is a placid grandmother in paler shades of the same color triad, and on the far right is a female servant holding an infant decked out in patriotic ribbons. At the far left, a grandfather enjoys a dish of berries, while the paterfamilias, a crippled Union veteran, sits in the shade with crutches propped against his chair. Finally, an Italian organ grinder has just arrived, accompanied by a little barefoot girl with a tambourine. As the organ grinder’s monkey begs, the younger daughter, holding a coin, shrinks back against her mother’s skirts, while her distracted little brother offers the unkempt stranger a glass of milk.

The adult women in the center all wear golden thimbles on their middle fingers, the mother’s pointing directly down toward an American flag at the bottom edge of the composition. The flag lies in two pieces: stripes in a rumpled heap, starry field reposing on a regal purple footstool. Closest to the picture plane is a sewing basket filled with thread, scissors, a pin cushion, and loops of golden, tasseled braid. The message is unambiguous: women, and not men, will stitch up the wounds of war and mend the nation’s fractured union.

In suggesting that women would play a vital role in healing the country, Spencer’s painting celebrates a newfound agency. During the Civil War, the boundaries between home and the outside world steadily fell away as women by necessity took the places of the men who had gone to battle, hundreds of thousands of them never to return alive.11 Women sewed flags, made shirts, rolled bandages, worked in government arsenals, ran family farms, filled bureaucratic positions, nursed the wounded, oversaw the great sanitary fairs that raised money to improve conditions for Union troops, and even disguised themselves as men so that they, too, could be soldiers.12 Working-class urban women had long labored outside the home, but now their middle-class sisters joined the ranks of the employed, fueling feminist hopes that women’s voting rights and full participation in public life would soon follow. Sidelined, the men in Home of the Red, White, and Blue—one elderly, one maimed—have only bit parts to play in the new order.

Spencer’s women are ready to take on the world. But the world has already come to them in the form of the Italian organ grinder and his little crew. How have these shabby figures wandered into this sheltered middle-class garden? During the postwar years, the increasing flow of impoverished Italian immigrants into the United States had become a major source of alarm. Poorly educated tenement-dwellers, many of them begged for money by playing their barrel organs or violins on the street. To the native-born, they appeared shiftless and threatening. Just as Johnson’s black fiddler—on his way somewhere else—is clearly not at home in the rustic northern farmer’s kitchen, Spencer’s itinerants do not fit in. Are they welcome in the land of the red, white, and blue, or, as indigent aliens, do they represent a danger to the fragile stability of post-war America? Spencer does not say, and indeed, nothing in the picture is resolved. The flag lies in two pieces; women, for all their symbolic agency, are still confined to the domestic realm. At once allegory and genre painting, Home of the Red, White, and Blue portrays a postwar landscape of change, where optimism and anxiety lie in uneasy balance.13

Before the war’s end, genre painter William Sidney Mount produced his very first still life, Fruit Piece: Apples on Tin Cups (Fig. 5), and donated it to New York’s 1864 Metropolitan Fair, a benefit for the United States Sanitary Commission’s war relief effort. The composition consists of two vividly realistic apples, solid and shiny, atop a pair of upended tin cups. Other than a small spray of green leaves to the left, there is nothing else in the dark and indeterminate space where the objects rest. Elemental in its simplicity, Mount’s painting is a departure from conventional American still lifes of the day, typically cornucopian extravaganzas of heaped and cascading fruits and flowers in fancy porcelain bowls or silver compotes—luxury artifacts intended for the dining rooms of the well-to-do.Mount’s imagery, by contrast, is so simple and humble that it might be more at home in the office of some regimental quartermaster. Yet it is rich in symbolism.

William Sidney Mount (1807–1868)

Fruit Piece: Apples on Tin Cups, 1864

In the nineteenth century, particularly in the North, the apple was ubiquitous and so abundant that Ralph Waldo Emerson (1803–1882) dubbed it “our national fruit.”14 As art historian Diane Dillon has written, Yankee soldiers longingly associated the apple with home; sometimes they even made mock apple pies in their army-issue tin dippers, like those on which the two pieces of fruit repose in Mount’s painting. The austerity of Mount’s design serves as metaphor for the austerity of life in the field and at the front, where rations were at best meager. The fingernail impression in the foremost apple and the wear on the cups’ surfaces are human imprints that stand in as surrogates for absent soldiers, who, like the apples, were “plucked in their prime and shipped out.”15 The apples—long associated in Christian cultures with Adam, Eve, and the legend of the Fall—suggest something else too about ordinary soldiers’ wartime lives. Like the unlucky pair who first ate from the tree of knowledge of good and evil, the unseen soldiers have fallen from innocence into dire experience.

The trauma of the war—that incalculably dire experience—prompted a retreat in American culture into dreams of lost youth and innocence reborn. Many artists catered to such longings by manufacturing wistful images of rural life in an idealized antebellum past. One of the most successful of these was John George Brown (1831–1913), whose immensely popular scenes of charming country children found an eager and receptive audience in the 1870s. Born in England, Brown immigrated to New York in 1853 and studied at the National Academy of Design. Taking a cue from American Pre-Raphaelites such as Thomas Charles Farrer (1838–1891), he perfected a highly naturalistic manner that gave vivid life to his wholesome rustic idylls.

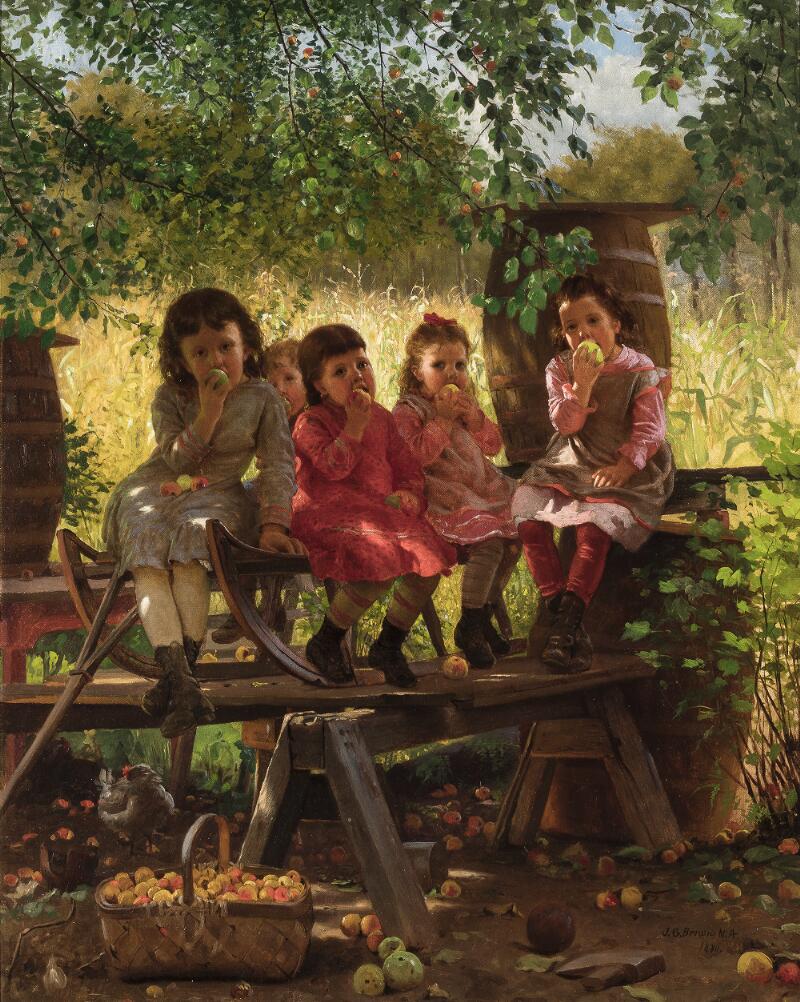

The Cider Mill (Fig. 6) well represents Brown’s winning style. In it, we see five little girls in an orchard. Each one is about to take a big bite out of a freshly picked apple. More apples lie in their laps, in a basket, strewn thickly on the ground. Dappled with spots of sunlight, the girls wear colorful stockings, short dresses, and pinafores. They sit perched on a sled that has been raised onto a board platform slung across a couple of sawhorses. Behind them stand several large barrels, and beyond is a stand of corn, brilliant yellow-green in the light.

John George Brown (1831-1913)

The Cider Mill, 1880

The girls seem to embody the sweetness and light of childhood innocence. Yet given the subject—“little Eves in an abundant Paradise,” as scholar Martha Hoppin puts it—there may be a sly subtext here.16 Five little Eves certainly promise more trouble than just one, and a literal fall might actually be imminent, given the combined weight of five solid little bodies, plus the heavy sled, supported only by those flimsy-looking boards. Then there are the barrels, presumably for storing the cider from the unseen mill. Consumed by adults and children alike in the earlier nineteenth century, cider was mildly alcoholic. Predictably, the drink became a target for the reformist temperance movement that gathered a new head of steam in the postwar decades.17 Brown’s girls are eating apples, not tugging from a jug. But they are self-absorbed, self-indulgent, unsupervised. What will happen when they grow up? Will they become proper wives, or independent and therefore threatening women? Underneath the sunny surface lurks a hint, perhaps, of anxiety.

Winslow Homer (1836–1910) also took up rustic subjects in the 1870s. A Bostonian who started out as an illustrator, Homer had been an artist-reporter during the Civil War. In the late 1860s and early 1870s, he turned to modern American life and modern American women, as in Croquet Scene (1866, Art Institute of Chicago), which depicts two stylish young women and a young man playing the newly popular game. But by the middle of the seventies, Homer had begun a steady retreat from present-day fashion, turning instead to pastoral imagery far removed from the excess, corruption, violence, and extreme social inequities that marked and marred America’s Gilded Age. Apple Picking (Fig. 7) is one of some thirty drawings and watercolors that Homer produced in the summer of 1878, working in the open air at his friend Lawson Valentine’s Houghton Farm near Mountainville, New York. It incorporates the same basic elements as Brown’s Cider Mill—fresh young country girls, a basket, an orchard, brilliant color and light—but as means to a very different end.

Winslow Homer (1836–1910)

Apple Picking, 1878

Two children stand arm in arm in full sunlight that bounces off their sunbonnets and jackets with almost blinding intensity. Before them is a band of deep green shade; behind, in duskier greens, the orchard. Above the figures dangle branches loaded with crimson fruit; red accents also dot the girls’ garments and the trees further back. There is no overt commentary here, no symbolism, story, allegory, moral, or sentiment. Homer treats the two girls as dispassionately as he does the grass or the trees. The passion in the painting is funneled into the artist’s act of looking, the process of transcribing visual sensations into washes, streaks, dabs, and lines of vibrantly contrasting, luminous hues. Anything not painted in the open air, Homer declared, was simply and palpably false.18

Brown’s Cider Mill postdates Homer’s Apple Picking by a couple of years. Brown may well have looked to Homer for inspiration: the two were friendly acquaintances and had studios in the same building on Tenth Street in New York City. In The Cider Mill, Brown backlit his figures just as Homer did, and he used the same device of down- ward-dangling apple branches. But where Brown looked backward, to the established conventions of genre painting—that is, ordinary people going about their daily lives in an unchanging social order—Homer moved beyond them, his art developing more and more into a record of the artist’s unique and original vision. Even though he broke the mold, Homer capitalized nonetheless on the old dream of American country charm and its intrinsic goodness. His children, wrote one critic in the 1870s, were “wholesome, hearty, and artless youngsters” reveling in “the freedom of their out-of-door existence.”“19 At one with nature, they would never change, never grow up, never leave home, never vote. In an anxious age of relentless social turmoil and progress—then and now—what could be more appealing?

-

See Elizabeth Johns, American Genre Painting: The Politics of Everyday Life (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1991), especially Chapter 1, “Ordering the Body Politic,” 1–23. ↩︎

-

G[eorge]. M[urray]., “Review of the Third Annual Exhibition of the Columbian Society of Artists and the Pennsylvania Academy,” Port Folio 2 (1813): 139–40. ↩︎

-

Rowena Houghton Dasch, “‘Now Exhibiting’: Charles Bird King’s Picture Gallery, Fashioning American Taste and Nation 1824–1861” (PhD diss., University of Texas at Austin, 2012), 187–193. ↩︎

-

Coined by the influential journalist John L. O’Sullivan in 1845, the term “manifest destiny” expressed the widespread conviction that Euro-American settlers were by divine sanction destined to expand across and possess the entire continent. ↩︎

-

There were also painters of frontier life, such as George Caleb Bingham (1811–1879) and William Tylee Ranney (1813–1857), who constructed a model of American identity based on rugged individualism, restless energy, and a will to dominate western lands. ↩︎

-

“The National Academy of Design,” The Crayon 6, no. 6 (June 1859): 191. ↩︎

-

One of the most notable of these paintings is A Ride for Liberty—The Fugitive Slaves, c. 1862 (Brooklyn Museum of Art), which shows a black family on horseback in a desperate flight to reach the Union lines. ↩︎

-

It is not known which of the two was the first one Johnson painted, though it was probably the white version, which is more of a study. Johnson said nothing about either painting. The Terra’s painting was not exhibited during Johnson’s lifetime and was sold out of his estate. ↩︎

-

This was a crucial question after the war. Reconstruction (1866–77) in the South was accompanied by federal legislation that abolished slavery, made all black people full citizens, and gave black men the franchise. Yet by the end of that period the majority of black people, most particularly in the South, had little to celebrate: their social and economic status was scarcely improved, and in the South oppressive new laws relegated them to menial labor and brutally enforced their segregation from white society. ↩︎

-

Patricia Hills, “Painting Race: Eastman Johnson’s Pictures of Slaves, Ex-Slaves, and Freedmen,” in Teresa A. Carbone and Patricia Hills, Eastman Johnson: Painting America (New York: Rizzoli, 1999), 121. ↩︎

-

It is estimated that as many as 750,000 lost their lives in the war—about 2 percent of the population—and thousands of survivors were permanently maimed. ↩︎

-

These fairs operated under the aegis of the United States Sanitary Commission, organized by prominent citizens in the North and signed into law on June 18, 1861. The purpose of the USSC was to create a corps of volunteers charged with visiting Union Army camps and hospitals to ensure that they were adhering to proper hygienic standards. The sanitary fairs, run mostly by women, raised money for food, blankets, and medical supplies to supplement what the chronically over-extended War Department was able to provide. ↩︎

-

For additional details, see Sarah Burns, “Rending and Mending: The Needle, the Flag, and the Wounds of War in Lilly Martin Spencer’s Home of the Red, White, and Blue,” in Peter John Brownlee et al., Home Front: Daily Life in the Civil War North (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2013), 99–125. ↩︎

-

Ralph Waldo Emerson, “Country Life,” in The Later Lectures of Ralph Waldo Emerson, 1843–1871, vol. 2, eds. Ronald A. Bosco and Joel Myerson (Athens: University of Georgia Press, 2010), 55. ↩︎

-

Diane Dillon, “Nature, Nurture, Nation: Appetites for Apples and Autumn during the Civil War,” in Brownlee et al., Home Front, 135–37, 145. ↩︎

-

Martha Hoppin, The World of J.G. Brown (Chesterfield, MA: Chameleon Books, 2010), 107. ↩︎

-

Ibid., 107. ↩︎

-

George William Sheldon, “Sketches and Studies,” Art Journal (April 1880): 107. ↩︎

-

“The Water Color Exhibition,” The Sun, February 16, 1879. ↩︎