William Groombridge (1748-1811)

View of a Manor House on the Harlem River, New York, 1793

For Groombridge’s painting, and early American painting more generally, reward closer consideration less as evidence for what is to come in the history of American art than as pictorial attempts to deal with contemporaneous issues and realities. In this sense, the term “early American” can be unhelpful, obscuring the fact that these paintings were, of course, the contemporary art of their own time. And for the artworks addressed in this essay, all painted in northeastern states (or their precursor colonies) during the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, the issues and realities of their historical moments are also those of modernity: historical experience and “historicity” (a sense of the present moment within history); the navigation of communal identities and subjective experiences; the role of art within a world of technological, economic, and political change. Even if Groombridge’s image now seems unrecognizable to us as a view of Manhattan, and few of the concrete realities of early American life remain, the issues raised by these works remain pressing today. Present realities are always linked to past ones, as early Americans understood, despite longstanding myths of America as a place of virgin soil, self-reliance, wholesale reinvention, and no second acts.

For Groombridge’s painting, and early American painting more generally, reward closer consideration less as evidence for what is to come in the history of American art than as pictorial attempts to deal with contemporaneous issues and realities. In this sense, the term “early American” can be unhelpful, obscuring the fact that these paintings were, of course, the contemporary art of their own time. And for the artworks addressed in this essay, all painted in northeastern states (or their precursor colonies) during the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, the issues and realities of their historical moments are also those of modernity: historical experience and “historicity” (a sense of the present moment within history); the navigation of communal identities and subjective experiences; the role of art within a world of technological, economic, and political change. Even if Groombridge’s image now seems unrecognizable to us as a view of Manhattan, and few of the concrete realities of early American life remain, the issues raised by these works remain pressing today. Present realities are always linked to past ones, as early Americans understood, despite longstanding myths of America as a place of virgin soil, self-reliance, wholesale reinvention, and no second acts.

In 1793, when he painted the Terra Foundation’s picture, Groombridge (1748–1811) was in his mid-forties and had just arrived in New York after an artistic career in England as undulating as the topography of Manhattan Island.1 Born in Kent, he had started to show his landscapes and portraits in London during his mid-twenties, but critical response was mixed: for some, his views “of the most remarkable structures, and situations in Great Britain” were “not unworthy the notice of the best painters,”2 while others found his “tolerable Landscapes” to have limited appeal.3 Spells in debtors’ prisons testify to his professional difficulties,4 and the loss of his wealthy patron in a riding accident probably left him with few prospects, as his book of sonnets on themes of melancholy and despair, published in 1789, suggests.5 His migration to America four years later would have been a chance to start afresh.

Unfortunately for Groombridge, there were few patrons for land-scape painting in America, and he took to selling his works by public raffle, which might explain why his palette became more vivid and his handling of paint more bold.6 Inklings of this transformation can be found in View of a Manor House, where the modest subject is the pretext for a sustained and energetic display of painterly artifice, highlighting the artist’s presence upon this (to him) new terrain.

What is this painting’s subject matter though? At sunset, we look northeast from an elevated position across some uncultivated pasture, a muddled patchwork of enclosed land, and a quiet riverscape. Apart from the large house at the far left and the distant church steeple to the right, there are few landmarks to identify the location.7 Yet comparison with historical images suggests that, as the label on the reverse of the canvas claims, this is a view across the Harlem River, from Manhattan toward the Bronx.8 As his View of Maidstone, Kent (c. 1770, Government Art Collection, London, UK) shows, the view across the water toward a distant steeple, complete with cattle, farmer, and shaky perspective, was a formula that Groombridge had previously applied to his English landscapes. Those draw heavily on the influence of the British landscape painter Richard Wilson (1714–1782), who applied the pictorial conventions of Old Master landscape painters such as Claude Lorrain (c. 1600–1682) to British terrain.9 Groombridge followed both Wilson’s example and Lorrain’s in his depiction of north Manhattan, staging the landscape from foreground to background through successive receding planes, visual pathways and destinations, and the changing tones of aerial perspective.

That said, Groombridge’s image is no pastoral idyll. Down by the riverside, awkwardly positioned in the no-man’s land of the painting’s mid-ground, lie roughly a dozen sunlit buildings. Judging by the smoke from their chimneys, some are probably homes while others suggest the rural barns, storehouses, mills, and slave quarters that still dotted most of the island. The relationships of these buildings to each other, to the oddly shaped parcels of land before them, or to the houses we see in the left foreground, are unclear. This is a landscape structured by separate, possibly competing, small-scale interests; a haphazard settlement whose ideal unit would seem less the partly visible grand house on the left with its hillside prospect than the timber cottage tucked away among the escarpments below. Like the lone figure determinedly going about his business, this cottage and its tightly fenced smallholding offer an emblem of self-interest, self-sufficiency, and their corollary—isolation.

The exuberantly painted sky and variegated weeds of the patchy hillock—a conventional motif of uncultivated nature within late eighteenth-century picturesque landscape imagery—distract us from this fragmented social landscape. Groombridge devoted significant space and energy to these areas, which offer the comforting visual pleasures of humble nature, glowing sunset, and painterly brushwork. But there remains a strangely intrusive, insistent form at the bottom left: a blank gray wall of uncertain height and function. Reading the image from left to right, we stumble on it every time. It is a piece of fortification, a reminder that this area had been the site of violent and decisive warfare during the first months of the American Revolution.

Less than two months after the Declaration of Independence in July 1776, and following the heavy defeat of the Continental Army at Brooklyn, British troops captured the city of New York and advanced toward the forts established in upper Manhattan by George Washington. After a series of battles (all but one defeats for the American cause), Washington retreated with his troops through New Jersey to Pennsylvania. Though the tide later turned in Washington’s favor, Manhattan and its surroundings remained an area of British occupation, confiscation, and destruction, as well as American (including Mohican) resistance for the remainder of the war—nearly seven years.

Groombridge’s painting therefore places us in what had recently been a war zone. Somewhere behind us would have stood the forts that guarded the Hudson River, and before us would have been further fortifications overlooking the Harlem River. Material detritus from the war covered the area into the twentieth century.10 Yet only that gray wall to our left, and the seemingly ruined state of one of the white houses on the shore, suggest a history of conflict. The location’s specific and momentous historical significance remains almost unspoken. It is possible that the artist knew little of this specific history, though he would obviously have been aware of what his composition fully avoids: New York City, some ten miles away, any thought of which is impeded by the picturesque device of the verdant slope to our right.

Quiet and/or ambivalent about the effects of modern history upon the American landscape, Groombridge was more forthcoming with his claims to artistic presence and to the painterly representation of a present moment, as his subtle invocation of enshrined artistic precedents, the amount of canvas given over to the representation of the sky, and the alternately smoothed and gestural quality of his brushstrokes all suggest. Perhaps the deeper meanings of his new surroundings, in the still emergent United States of America, had yet to be understood. In its emphasis instead on presence and the present, Groombridge’s painting is comparable to the works of earlier, self-consciously colonial artists. The master of this mode was John Singleton Copley (1738–1815), whose Portrait of a Lady in a Blue Dress (Fig. 2) and Portrait of Mrs. John Stevens (1770–72, Terra Foundation for American Art) offer bravura displays of both the material realities enjoyed by some colonial subjects and the power of the artist’s eye and hand to depict them.

John Singleton Copley (1738-1815)

Portrait of a Lady in a Blue Dress, 1763

Copley’s colonial-era portraits are never simply records of things seen, however—they are also expert pictorial constructions of nuanced subjectivity, in which his sitters often seem to be caught between emotional states. In the Portrait of a Lady in a Blue Dress, psychological depth is conjured by the tension between the near-profile view of the sitter’s head and the near-frontal presentation of her upper body, the latter twisted in our direction as if competing with the head for our attention, especially at her bust, where a huge individual pearl surrounded by fleshy pink ribbon seems to face directly toward us. The conflict between gender and selfhood, between public meaning and private experience—increasingly understood to be the lot of modern women—is given visual form by Copley. This conflict is further manifest in the tension between her facial expression (eyes seemingly lost in thought, the signs of a smile playing upon her lips) and the lace band tied tightly around her neck as if reining in the individuality suggested by her face.

This dual engagement with forms of inner experience and art’s power to articulate them would be instrumentalized in the early nineteenth century, as art was called upon to shape subjectivities toward the common good of specifically “American” communities. For artists as diverse as the rural Quaker preacher Edward Hicks (1780–1849) and the highbrow urbanite Washington Allston (1779–1843), who both worked during the second quarter of the century, painting promised to transform its viewers.

Hicks’s religious beliefs largely condemned art as a luxury; the one permissible end of painting, in his view, was moral and spiritual reformation. A Peaceable Kingdom with Quakers Bearing Banners (Fig. 3), one of sixty-two versions of this subject he produced over three decades, seeks that end through a visual allegory of Old Testament scripture, specifically Isaiah 11:6, “The wolf also shall dwell with the lamb and the leopard shall lie down with the kid; and the calf and the young lion…, and a little child shall lead them.”

Edward Hicks (1780–1849)

A Peaceable Kingdom with Quakers Bearing Banners, c. 1829–1830

This prophesy foretells the peaceful coexistence that will follow from religious observance. But Hicks does more than simply illustrate this passage: he deploys the material properties of paint with care, even love. Scripture is the excuse for his detailed depiction of fur, bark, cloth, and grass, using a variety of brushstrokes and painterly techniques. And yet, for many Quakers, painting was “a link in the chain of anti-Christian foibles next to music and dancing.11 If Hicks was to use paint as the vehicle for its own elevation into spiritual truth, that transformation had to be dramatized. He therefore allowed paint’s “base” state some free play, so that the inherent conflict in Quaker belief between paint’s rich materiality and its revelatory potential could be overcome. This may explain Hicks’s practice of inscribing (sometimes covering) the solid frames of his paintings with phrases that seek to distill the work’s meaning. The frames are integrated into the paintings they surround, much as religious strictures might curb the sensory pleasures of the viewers to whom the paintings are addressed, though the thick golden paint and stylized form of their inscriptions suggest that such pleasures and their potentially negative influence were hard for a painter to avoid.

Influence had been an important dynamic in Hicks’s life. He had learned to paint as a thirteen-year-old apprentice in a carriage-making workshop, where he had also learned to swear, drink, and submit to “licentious lewdness.”12 In his memoirs, he credited the religion of his Quaker foster parents with pulling him back from the brink and providing him with a solid community and a strong moral framework.

Quakerism is founded on the belief that every individual can forge a direct relationship with God. Believers are effectively their own priests, administering to their souls under the combined influence of direct experience of God (“the Inner Light”), Bible study, a purified way of life, and the speeches of fellow worshippers and unpaid preachers—hence the religion’s proper name, the Society of Friends. By his early thirties, Hicks had become renowned for his ability to explain Christian doctrine “in a clear and forcible manner, to large assemblies of different denominations.” From 1827 (shortly before the Terra Foundation’s Peaceable Kingdom was painted), his sermons disseminated the radical beliefs of his cousin Elias Hicks (1748–1830), who argued that Christ’s primary meaning was not as the man whose suffering compelled religious obedience, but as a symbolic model for the “Christ Within” each believer, accessed through individual encounters with the Inner Light. This reinterpretation of Christ’s role caused a schism within the Society. It also placed unprecedented emphasis on self-regulation and self-salvation. Little wonder then that Edward Hicks’s sermons fervently promoted self-interrogation, humility, commitment to God, and vigilance against living in “a lukewarm and libertine condition.” He addressed himself particularly to wayward souls—“the returned prodigal, the sinner awakened to a sense of his guilt.”13

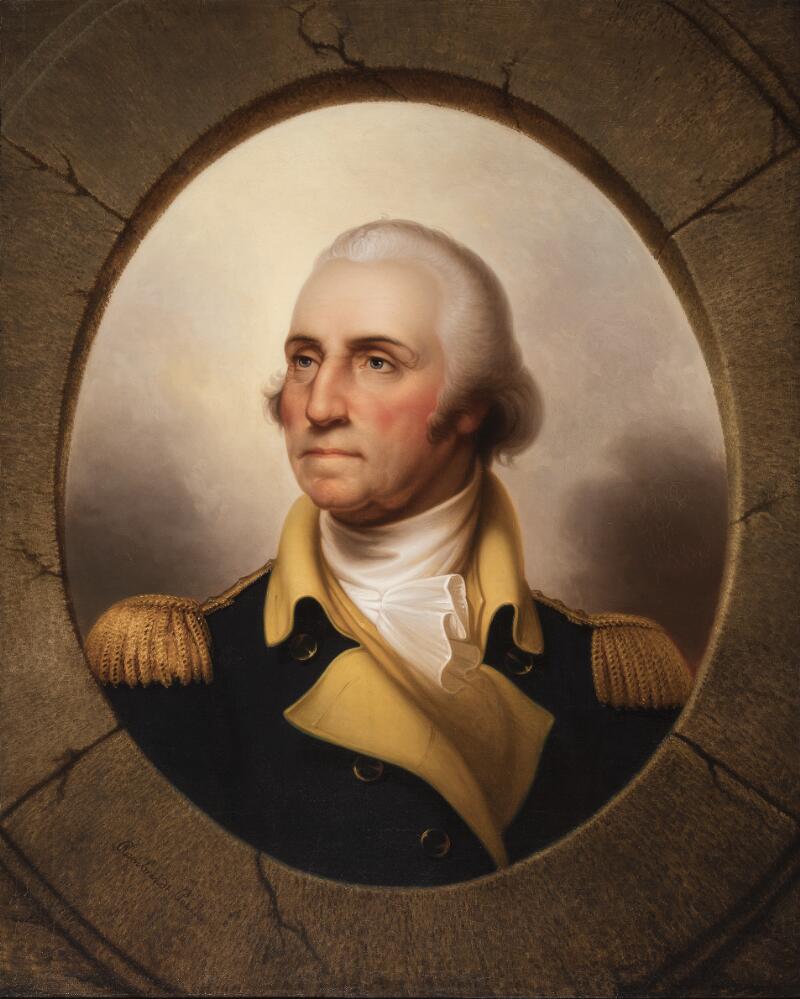

Communication is central to Quaker life, and it was as communication that Hicks’s “excessive fondness” for painting was permissible.14 The clarity of his Peaceable Kingdom paintings, along with the inscriptions on their frames, indicate his intention of delivering influential messages, in this case the prophetic significance of Isaiah 11:6. For Christians, the “child” in that passage is a prefiguration of Christ, and for Hicks, Christ was a spiritual model to be internalized by believers. Hence the figures’ seemingly adult features (even five o’clock shadow). Hicks’s understanding of Christian doctrine as a source for individual guidance and interpretation also explains the latitude he took in his Peaceable Kingdom pictures with the prophecy’s animal and human cast. On the left of the Terra’s painting, we see a large gathering of Friends, united on the path to heaven. Above them appear Christ, the Apostles, and angels bearing a banner promoting direct communion with God and universal peace. Among them stand William Penn (the seventeenth-century founder of& Pennsylvania) and Elias Hicks, bridging the Society’s past and present, as well as George Washington, the great unifying figure of the new nation.15

Beyond this potent symbolism, the painting’s highly worked surfaces and attentiveness to detail suggest an artist for whom the act of representing the natural world might also have been a form of worship. Visual truth and religious truth serve each other everywhere in Hicks’s picture. The forceful upward strokes which form the jagged splinters of the broken tree to the right underline its role as a sign of the rupture which had occurred among the Quakers, just as the dark green leaves that seem to grow from the tree’s healthy offshoot indicate the vitality of new energies. A similar story is told below, where Hicks depicted a fissure in the terrain, carefully suggesting its geological strata and fringe of yellowing turf. This turf contrasts with the lush grass immediately before us; like the storm clouds above, which have parted to reveal glowing pink and heavenly blue, or indeed the central iconography of beasts at peace with each other and with man, division and its resolution in fresh harmony are shown as productive processes, at once natural and divine. The profusion of natural detail helps articulate the picture’s central promise: that current tensions presage a healthy and peaceful future for the Society of Friends, on earth and in the heaven to which members are seen ascending at the left-hand edge. That the fulfillment of this promise requires ongoing inner vigilance is suggested by the leopard in the foreground. A wild jungle creature, its fierce red eyes stare directly at the viewer as its whiskers bristle with alertness. Yet the leopard also appears here as a symbol of self-control, stretched across the fore- ground, calm and collected. Only by adopting such an attitude, it seems, checking animal impulses with the kind of determined grip that the child maintains over the lion at his side, might we join the vision of heaven beyond.

Hicks worked outside the art worlds then proliferating in America’s northeastern cities, including nearby Philadelphia. His techniques and motivations are distinct, if not always divorced, from nineteenth-century art’s central institution, the art academy.16 There, a vision of art was promoted in which the articulation of internal and external truths required a sustained (and ideally direct) relationship with a quite different authority: European artistic precedent, specifically classical antiquity and the Italian Renaissance. Yet in the urban academy, as in the Quaker meeting-house, art was increasingly understood as a means to transcendence, for those viewers attuned to its meanings. In the case of Washington Allston, this sense of transformative possibility arose within the wider reconception of art and literature that took place during the cultural transition now known as romanticism. For professional artists and writers during the first decades of the nineteenth century, the primary function of art became the instigation of individual aesthetic experience, rather than the promulgation of public ideals through history painting, as had been argued since the seventeenth century. This redirected painting’s role in public life toward the refinement and recuperation of private sensibilities blunted (it seemed) by the cares of modern life.

Aesthetic experience and its recuperative powers are the subject matter of Allston’s Lorenzo and Jessica (Fig. 4), which depicts a moment from William Shakespeare’s drama The Merchant of Venice. In a quiet and magical interlude immediately after Shylock’s trial, we find ourselves transplanted from the hot and hectic Venetian courtroom to the cool twilight gardens of the villa to which Shylock’s daughter Jessica has eloped with her lover, Lorenzo.

Washington Allston (1779–1843)

Lorenzo and Jessica, 1832

The couple playfully argue over the associations of night: for Lorenzo, it is the time for true love’s expression; for his new wife, it is the time for romantic betrayal. She is restive and anxious, and Lorenzo commands musicians to play before uttering the soliloquy whose opening line is inscribed on the reverse of Allston’s painting.

How sweet the moonlight sleeps upon this bank! Here we will sit, and let the sound of music Creep in our ears. Soft stillness and the night Become the touches of sweet harmony. Sit, Jessica. Look how the floor of heaven Is thick inlaid with patens of bright gold.

In the penumbral gloom, we can just discern, from left to right, the structure of the villa, the couple, and the distant silhouette of the city. Jessica’s twisted, upright pose and downward gaze melt into the calm repose of her husband, who looks (like us) across to the horizon, his most active element the feather in his cap, which lifts with the cooling breeze. Only his hand gesture indicates his exemplary, didactic status in the scene: “Sit, Jessica.”

In the play, Jessica’s protestation that “I am never merry when I hear sweet music” is received by Lorenzo as evidence of her emotional depth, as he bids her look and listen. Given time, aesthetic experience is transformative, soothing wild feelings and savage hearts. Art has a unique power to refine the subjective worlds of those able to see it. Shakespeare’s scene was an appropriate source for Allston. After graduating from Harvard, he had sold his inheritance (his slave-owning family’s South Carolina rice plantation) to fund his artistic education in Europe, initially in England and then in France and Rome. Between 1800 and 1818 he lived and worked mostly abroad. By the time he resettled in Boston, he was almost forty years old. Though his artistic reputation preceded him (he had been elected an Associate of the Royal Academy), it had yet to be proven in the eyes of American patrons and critics. This was a challenge for an artist of Allston’s sensitive, “poetic” character—and his fortunes were mixed: while some of his canvases enjoyed considerable success, he abandoned others (most famously, his enormous and much-anticipated Belshazzar’s Feast) for fears about their public exposure.

Lorenzo and Jessica is an example of the kind of work most appreciated by Allston’s contemporaries. It is one of a sequence of paintings from the 1820s and early 1830s that center on single or paired figures (typically female), shown in states of reverie and reflection within natural settings, often as if listening to music. Many of these paintings are “cabinet pictures” of a size appropriate to intimate domestic display (just eighteen inches wide, Lorenzo and Jessica is the smallest of Allston’s exhibited works), and used many slow-drying layers of thin glazes that result in singing tones, subtle gradations, and soft suggestive effects.17 Their size, their portrayal of quiet leisurely repose, and their emphasis on pure aesthetic, sensory, and emotional experience made them popular among Boston’s wealthy merchants, for whom art had come to be seen as an antidote to life in the rapidly industrializing American city. Lorenzo and Jessica, for example, was bought for a notable sum (around $20,000 in today’s money) by the tycoon Patrick Tracy Jackson, one of the so-called Boston Associates whose fortunes were made by investing in the region’s burgeoning industries.18

The literary and artistic references of Allston’s more suggestive pictures appealed to Boston’s cultural elite. As a poetical prompt to the imagination, inviting us to inhabit the emotions of the lovers as they marvel (like us) at the luminous sky above, Lorenzo and Jessica invokes the metaphorical imagery and suffused coloristic manner of sixteenth-century Venetian artists such as Titian (c. 1485/90–1576) and Giorgione (c. 1477/8-1510). In doing so, the painting offers its viewers that valuable commodity—thought rare in 1830s American—“art.” Combining this historical influence with an identifiably modern attempt to suggest emotional and aesthetic responsiveness, such as might be experienced when listening to music with a lover at twilight, his work received close critical attention from other artists and writers, including Ralph Waldo Emerson (1803-1882) and other transcendentalists of the 1820s and ‘30s. For one such writer, who returned repeatedly to these works, Allston’s scenes of quiet reverie represented “a new class of pictures” that had “unlocked streams of thought and feeling, which, as unuttered presentiment, had burdened me before.”19

Offering close encounters with history, belief, and feeling, paintings produced in early America navigated currents that belie their present-day reputation as mere precursors to the more self-consciously “American” art that developed in the years around and after the American Civil War (1861-65). From Copley’s closely observed sitters to Allston’s aesthetic reveries, early American painting emphasized present experience while revealing the shifting role of art within the rapidly changing nation.

-

The most complete account of Groombridge’s career remains J. Hall Pleasants, “Four Late Eighteenth-Century Anglo-American Landscape Painters,” Proceedings of the American Antiquarian Society 52 (1943), 215–38. ↩︎

-

“The Exhibition,” Morning Chronicle and London Advertiser, May 14–15, 1784. ↩︎

-

“Royal Academy Exhibition,” London Courant Westminster Chronicle and Daily Advertiser, April 30, 1782, and May 2, 1782; “Exhibition of Paintings, Sculpture &c. at the Royal Academy,” St James’s Chronicle or the British Evening Post, May 15–17, 1787. ↩︎

-

See London Gazette, October 13–17, 1778, in which Groombridge is described as a surrendered fugitive, now in the King’s Bench prison. In 1783–4, Groombridge sent landscapes to the Royal Academy (including a view of Dieppe, a common resort for fleeing debtors) from an address within the precincts of Newgate prison. ↩︎

-

William Groombridge, Sonnets, the two last in Commemoration of the late Wm Jackson, Esq. (Canterbury, 1789). ↩︎

-

See William Dunlap, A History of the Rise and Progress of the Arts of Design in the United States, 3 vols. (Boston: C. E. Goodspeed & Co., 1918 [1834]), vol. 2, 176–7. ↩︎

-

The depicted steeple is most likely that of the Dutch Reformed Church in the Bronx. The large house at the painting’s left-hand edge was long identified as the Morris-Jumel Mansion, where the painting was discovered in the early twentieth century, but this identification has rightly been dismissed: the Morris-Jumel Mansion’s architectural form and style, and relationship to the river, differ from those in the painting; maps of the period show several large houses in north Manhattan. ↩︎

-

See the so-called British Headquarters Map (c. 1782, The National Archives, UK, MR1/463), reproduced as B F Stevens’s Facsimile of the Unpublished British Head Quarters Coloured Manuscript Map of New York & Environs (London: Malby & Sons, 1900). ↩︎

-

See William Groombridge, An Extensive River Landscape with Fishermen on the Banks (1782, Christie’s London, October 28, 2009, lot 105); A View of Canterbury (1787, Christie’s London, December 9, 2015, lot 156); A View of a Lake with Fishermen (1788, Yale Center for British Art, New Haven). ↩︎

-

See the Reginald Pelham Bolton Collection in the Dyckman Farmhouse Museum, New York. ↩︎

-

Edward Hicks, Memoirs of the Life and Religious Labors of Edward Hicks (Philadelphia, 1851), 71. ↩︎

-

Ibid., 36. ↩︎

-

Quotes in this paragraph are ibid., 7. ↩︎

-

Ibid., 31, 12. ↩︎

-

See David Tathan, “Edward Hicks, Elias Hicks, and John Comly: Perspectives on the Peaceable Kingdom Theme,” The American Art Journal 13, no. 2 (Spring 1981): 36–50. ↩︎

-

See Ellwood Parry, “Edward Hicks and a Quaker Iconography,” Arts Magazine 49, no. 10 (June 1975): 92–4. ↩︎

-

See Joyce Hill Stoner, “Washington Allston: Poems, Veils, and ‘Titian’s Dirt,’” Journal of the American Institute of Conservation 29, no. 1 (Spring 1990): 1–12. ↩︎

-

See The Athenaeum: Journal of English and Foreign Literature, Science, and the Fine Arts, no. 846 (January 13, 1844): 41; and Nathalia Wright, ed., The Correspondence of Washington Allston (Lexington, KY: University Press of Kentucky, 1993), 337. ↩︎

-

Elizabeth Palmer Peabody, “Allston the Painter,” American Monthly Magazine, n.s., 1 (May 1836): 435–46, and Last Evening with Allston, and Other Papers (Boston: D. Lothrop & Co, 1886), 46–7. ↩︎