As the coincidence with the Civil War suggests, the taste for landscape was never independent of larger currents of American history, especially the ongoing debate on the nation’s relationship to the land and its diverse, contradictory values—strategic, patriotic, economic, domestic, religious, scientific, philosophical, experiential, environmental. In the twenty-first century, although landscape has subsided as the premier genre of American painting, the land and its image remain sites for a bewildering variety of visual practices, from Hollywood sets and picture postcards to land art, topographical photography, eco-poetics, geographical documentary, geo-localized visualization, advertising and business concerns of all kinds, as well as a variety of activist efforts. Even as contemporary artists and critics deconstruct the “high landscape” of the nineteenth century and its perceived affinities with the ideologies of Manifest Destiny or Nature’s Nation, its enduring appeal testifies to the continuing significance of visions of the land, the social realities they transfigure, reveal, or disguise, and the prospects for escape, refuge, or reform they offer.1 The following pages suggest some of the complexities of this relationship between landscape and history.

For a starting point I use Notes on the State of Virginia, a major early description of American land by Thomas Jefferson (1743–1826). Published in 1785 in response to a questionnaire by the French diplomat François Barbé-Marbois (1745–1837), this text embodies an economic and political approach to the state of Virginia, including a consideration of its indigenous population’s history and a blueprint for the social and institutional organization of American democracy. It is not a treatise on landscape—the word does not appear in the book. As historian James P. Ronda writes, the appreciation of nature and the beautiful is a “secondary” concern for Jefferson: he “did not merely describe rivers; he judged them” in terms of utility, i.e., navigability.2 Yet he did not refrain from aesthetic judgment, albeit as a secondary and momentary consideration. In Query IV (“A Notice of its Mountains?”), discussing the geological history of the Blue Ridge and the marks of “disrupture and avulsion” displayed by rock piles on the edges of the Shenandoah Valley, Jefferson pauses to note the “different character” of the “distant finishing which Nature has given to the picture.” The mountain “being cloven asunder, she presents to your eye, through the cleft, a small catch of smooth blue horizon, at an infinite distance in the plain country, inviting you, as it were, from the riot and tumult roaring around, to pass through the breach and participate in the calm below.” “Here,” concludes Jefferson, “the eye ultimately composes itself; and that way too the road happens actually to lead.”3 This passage reveals an incipient interest in landscape as a separate value, amid a utilitarian and policy-driven description of the land. Many landscape pictures of the nineteenth century embody visions that similarly arise from temporary retreats, abstractions from the constantly evolving and often disruptive events of history. The gaze moves beyond the foreground, through a cleft, toward a smooth horizon, and obtains a moment of calm contemplation away from the “tumult” of the here and now. The vision of a higher, more serene realm evoked by landscape is only momentary, however, for the road leads on and calls the viewer back to practical prospects.

Although topographical views and pictures of local interest were already common by 1800, it was not until the 1820s, with the singular influence of the English-born painter Thomas Cole (1801–1848), that the type of vision recorded by Jefferson began to take shape in painting, eventually fostering a larger taste for landscape and its cultivation. Landscape with Figures: A Scene from “The Last of the Mohicans” (Fig. 1), one of Cole’s first pictures inspired by Hudson Valley scenery, presents a deep, strongly contrasted vista of a densely forested, mountainous landscape seen in receding grounds, highlighted toward the center by streaks of sunshine pouring through a stormy sky.

Thomas Cole (1801–1848)

Landscape with Figures: A Scene from "The Last of the Mohicans", 1826

A shaft of light falling on the foreground reveals a rocky outcropping, framed by tortured tree shapes in autumn garb which functions as a picturesque stage for the “scene.” This is the climactic moment of American author James Fenimore Cooper’s (1789–1851) just-published novel, The Last of the Mohicans, which inspired three further paintings by Cole. On the rocky center stage stands the American pioneer hero Hawkeye, aiming his rifle at the Huron chief Magua, who hangs from a cliff edge at right as he tries to flee after brutalizing his British captive. Cora Munro, seen in a white dress, lies dying on the ground next to her beloved, the Mohican Uncas. This action on the rock, however, occupies a very small portion of the canvas, which is not large, so that the characters are tiny and the details hardly legible without reference to the novel. The vast, wild landscape engulfs the figures. As Terra Foundation curator Peter John Brownlee notes, the captivity narrative, which Cooper’s romance reimagined as a more abstract epic of American history, is overwhelmed by “the greater dramatic sublime of the natural world.”4 Indeed the split structure of the view confines narrative and visual complexity to the extended foreground, which abruptly breaks into a majestic and serene background, with the flat valley bottom receding at the left of a massive range of rounded hills toward a distant horizon where the sky is clearing. As in Jefferson’s description, this distanthorizon is where the eye “composes itself,” and where the road “happens to lead.” But which road? Leading where? Landscape takes us into history, although after the last of the Mohicans has died, the question of whose history remains uncertain.

This work by the painter who soon came to be recognized as the founder of the “native” American school may function here as a program of sorts, albeit paradoxical, for the extraordinary expansion of landscape art that followed. The landscape is awesome, though its exact locale is unspecified and not easily identified. The Hudson River setting it celebrates combines elements of the picturesque, the beautiful, and the sublime, thus offering a lesson in the aesthetics of landscape; but the topography is largely imaginary. As an invitation to cultivate a taste for the wilder aspect of American scenery, which Cole promoted in painting and in his landmark essay of 1836, it is rather generic and more representative of European ideas than concrete American sites and circumstances.5 The anecdote it claims to illustrate comes out of a work of literary fiction, which itself, though credited with inaugurating a landscape tradition in American literature, offered highly stylized renditions of places like Lake George and Glens Falls, and was similarly concerned with a “quest for nationality”—an intellectual competition with European models—above and beyond its attachment to American landscapes. The very fact that this picture presents itself as illustrative—as a painting “after” a novel—would seem to defeat Cole’s own claim for the visionary, reformative, and purifying value of landscape. Its overt narrative motif—the demise of Native American civilization—is more explicit about the historical origin of the American “new land” than any of the paintings that follow. As a composition of massive natural shapes superimposing a drama of light, color, and volume on the tiny figures of Uncas and Cora, it inaugurates a form of art that for at least half a century would glorify landscape over history, while consistently signifying this history, even if indirectly, and the need to cultivate a taste for landscape as a bulwark against the perils of human affairs.

The pictures I discuss below were painted decades after Landscape with Figures, in the short span of time between 1864 and 1876; they belong to the peak period of landscape art in America, between the immediate antebellum years and the Gilded Age. There are multiple contexts behind this boom in landscape painting, which the pictures mostly fail to register, at least explicitly—though in most cases investigation will uncover them.

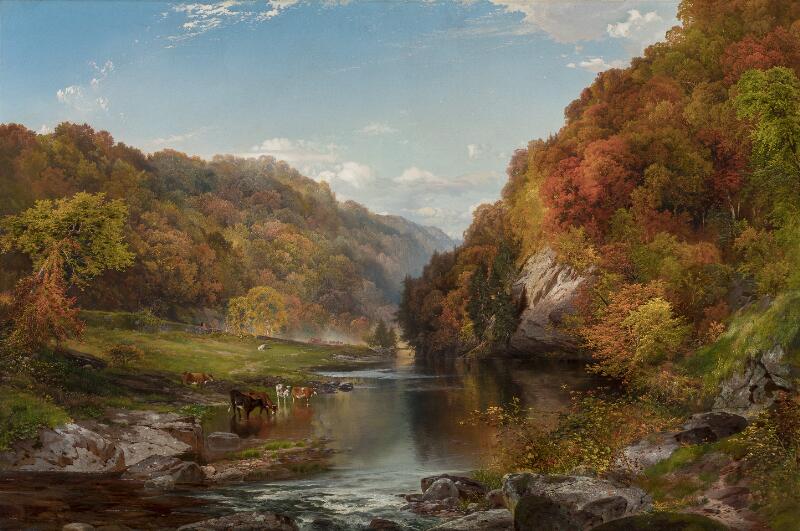

Slavery and the plantation economy, abolitionism and the strife between North and South, and the devastations inflicted on the people and land south of the Mason-Dixon Line, so vividly recorded in narratives, prints, and photographs of the time, are conspicuously absent from Thomas Moran’s (1837–1926) Autumn Afternoon, the Wissahickon (Fig. 2), probably the most striking among a series of brilliantly colored autumn views the Philadelphia painter devoted to a local creek in 1863–64.

Thomas Moran (1837–1926)

Autumn Afternoon, the Wissahickon, 1864

Although Moran’s detailed view refers to a specific spot, the painting’s rich, saturated palette and strong balance of lights and shadows, emphasizing nuances of foliage and reflections on the water, are reminiscent of Thomas Cole. Born in England, like Cole, Moran admired and emulated his forerunner, and was eventually recognized as his true heir. He belonged, however, to a later generation that enjoyed the benefits of professionalization and an expanding market for art in Philadelphia and other cities. Moran painted the Wissahickon views after visiting England to study the work of J. M. W. Turner (1775–1851) and other contemporary masters; he would go again before embarking, in the 1870s, on expeditions to the Western frontier. Like other versions of the scene, Autumn Afternoon was painted on commission; it was his most expensive work at that time. Whether or not the painter, as art historian Diane Dillon suggests, had the war in mind when creating this virtuoso play of light on stream and foliage, with cows placidly wading in the calm, luminous water, and no sign of industrial modernity whatever, such a glorious image would certainly “have offered visual escape to eyes weary of war.”6 If indeed landscape painting was seen as an “escape” from the war, it is a testament to the curative virtues—or the distractive powers—of the genre. Those “weary eyes” would have been exposed to the unprecedented saturation of visual information that characterized American culture in the 1860s, which made the war, for patrons of art as for many others, a spectacle to be confronted or avoided.

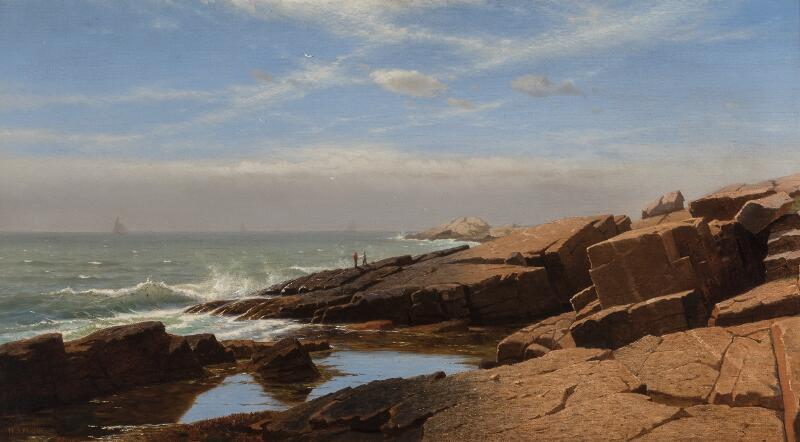

Exactly contemporary and in certain ways comparable to Autumn Afternoon is the smaller canvas by Fitz Henry Lane (1804–1865) entitled Brace’s Rock, Brace’s Cove (Fig. 3), also one in a series of several similar pictures of the same spot made over a short period of time at the height of the Civil War—though this particular version of the cove and rocks near Gloucester, Massachusetts, differs from the others for unknown reasons. Similar to Moran, Lane attached himself intently to a site or area—in this instance his native Gloucester, at other times coastal towns in Maine—that offered rich potential for landscape as well as social and financial support for pictures, painted or printed.

Fitz Henry Lane (1804–1865)

Brace's Rock, Brace's Cove, 1864

What is obviously different is the style and mood of the painting. Lane was handicapped from youth and prevented from traveling. He made himself known primarily as a marine painter and it was for his concentrated, purified studies of light and hue in sky and sea, almost bordering on abstraction, that he later became identified with the style known as luminism. The palette of Brace’s Rock is as subdued, restrained, and almost stark in its contrasts as Moran’s is exuberant, although the orange sunset ray that illuminates the rock formation in the center also highlights a small shrub, at left foreground, and pebbles on the beach at right that are discreet reminders of Lane’s affiliation with the Hudson River style. Yet here the eye is not drawn toward a vast prospect in which to find “composure,” but confronted instead by the lack of depth—a limited horizon, the dark silhouettes of rocks almost barring access to the cove—and by the wreck at center foreground and the feeble tide behind it. Whether or not we should read Lane’s insistence—especially marked in this version of the composition—on the decaying skeleton of a boat as a metaphorical emblem of the nation’s dismemberment, certainly the painting, one of the artist’s last, can be plausibly interpreted as a dark, yet quiet allegory of mortality. The repetition of this motif across several canvases again points to the taste of patrons who, toward the end of the Civil War, sought out landscapes of various styles and moods as malleable, supple expressions of American identity and its torments.

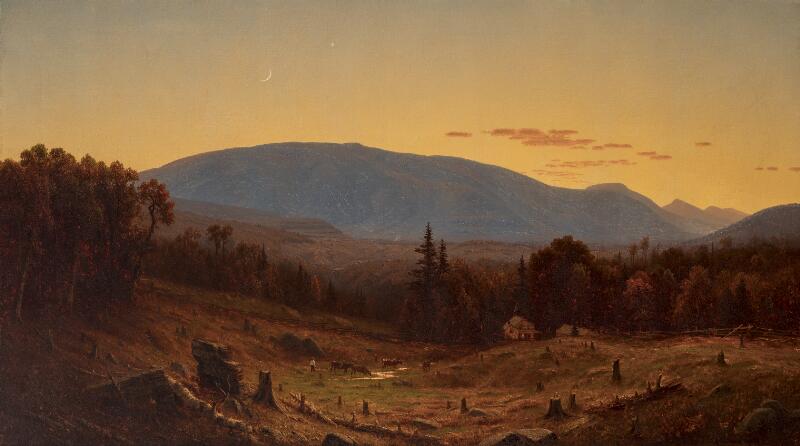

The remarkable ability of the landscape genre to adjust to shifting cultural needs and tastes over several decades is demonstrated by the resurgence in the East, immediately after the conflict’s end, of a style of pictures in which the wounds of war appear all but forgotten, or at least yield to a form of pastoralism now fully consistent with the lifestyle of what the Norwegian-American sociologist Thorstein Veblen (1857–1929) called, somewhat later, the “leisure class.” Consider Alfred Thompson Bricher (1837–1908)—born in New Hampshire, later resident in New York, and regarded as an important representative of the Hudson River school’s second generation—and his painting Lake George from Bolton’s Landing (Fig. 4).

Alfred Thompson Bricher (1837-1908)

Lake George from Bolton's Landing, 1867

Bricher’s wide, panoramic view depicts a location made famous by The Last of the Mohicans, and since the opening of rail service in 1849, a favorite holiday destination of New Yorkers and a choice topic for painters catering to the growing New York market. Even the subtle allusions to conflict tentatively identified in the Lane and Moran paintings are absent here. The composition echoes the classic formula, with a busy, rocky foreground flanked by solitary trees opening out onto a long perspective, guided by the gentle meanders of a stream toward the village of Bolton’s Landing and then the far distance where, in a haze, lie the calm expanse of the lake and the large rounded tops of the Adirondack range. Around the center of the painting, at middle ground, are gathered markers of civilization: the forest has been cleared, there are cattle grazing, fences bordering the grass areas, a bridge crossing the stream, a plume of smoke suggesting life in the small town’s dwellings. The “action” of the painting, however, at center foreground, revolves around two women in elegant excursion attire, one sitting and holding a travel guide or sketchbook, the other in a long pale dress, standing and perhaps posing for her companion, each in an attitude of communing with nature.

The contrast with both the grand style of Cole’s Landscape with Figures and the somber mood of Lane’s Brace’s Rock, Brace’s Cove is striking. As in similar landscape pictures of this period, signs of history are visible but subdued, nowhere as pressing as they were in Cole’s paintings of the 1830s. Just two years after the Battle of Appomattox Court House effectively ended the Civil War, and as the federal policies of Reconstruction in the South and conquest in the West were in full force, for Bricher and his New York upper-class market, landscape had become not just a rewarding genre of painting but a fully legitimate, self-contained, even self-reflexive cultural practice. No longer a momentary pause on the road or a respite from private or public grief, it was now the object and meaning of travel. Lake George would remain a sanctuary of landscape art for decades to come; during World War I (1914–1918) American photographer Alfred Stieglitz (1864–1946) and his circle made it again a privileged site for revelations of timelessness. In the decade or two after the Civil War, most successful landscape painters worked in or close to the East Coast settings where they grew up, lived, and found patronage. Though Boston and Philadelphia had their share of this durable phenomenon, the Hudson River school might more aptly be named the first New York school of painting, as art historian Angela Miller has demonstrated.7 One consequence of the dominance of New York—state and city—and the East Coast generally in the taste for what we might call the genteel style of landscape is the relative absence of the western United States in its corpus.

It was during and immediately after the Civil War that the United States Congress passed several landmark acts giving a decisive push to westward expansion and popular conquest of “new lands,” including the Homestead Act (allotting plots of land to settlers) and Railroad Acts (ceding large land grants to railroad companies to build transcontinental lines). In the field of landscape painting, the most vivid reflection of the great march westward lies in the work of the German-born artist Albert Bierstadt (1830–1902), who almost single-handedly created a genre of monumental mountain views, especially of the Sierra Nevada, along with epic scenes of emigrant wagon trains and romantic visions of pastoral Native Americans resting in timeless wilderness environments. As often noted, the numerous pictures of Yosemite Valley in Northern California that Bierstadt painted and exhibited during the Civil War, just as the site was declared a public recreation area, fed a redemptive rhetoric that obliterated the violence of war and conquest, and was largely compatible with the radical Republican ideology behind the Railroad Acts and “Go West” campaigns. Still, if such rhetoric was associated with the entry of Western landscapes into American visual culture, this was primarily achieved in the 1860s and 1870s not by painters but by illustrators, engravers, photographers, and stereographers, first in California and then in the entire area of the Western frontier. After 1870, any attempt at incorporating Western scenery within the growing canon of New York–style landscape had to demarcate itself from this profusion of popular visual matter.

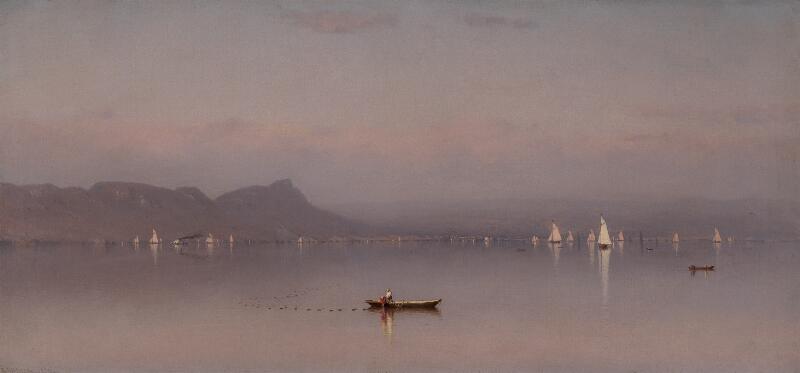

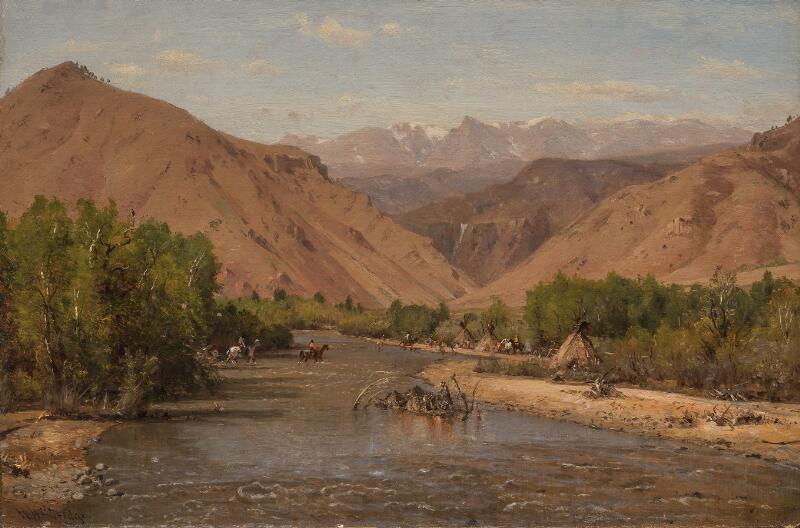

This would seem to be the case with the last picture discussed here, Worthington Whittredge’s (1820–1910) Indian Encampment (Fig. 5), painted some time between 1870 and 1876 probably in the artist’s studio in New York from sketches made on one of several trips he took to the West in the years after the Civil War.

Worthington Whittredge (1820–1910)

Indian Encampment, c. 1870–76

By this date Whittredge, who had started as a sign painter and a daguerreotypist before traveling to Europe to study in Düsseldorf, was one of the senior masters of the American landscape tradition, indeed one of the leaders of the New York school and president of the National Academy of Design, its semi-official home, from 1874–75. In later years his style would shift under the influence of the Barbizon school and then impressionism, but Indian Encampment, despite its small size, may be read as a kind of recapitulation of the genteel landscape tradition, its remarkable successes and its inherent paradoxes. The composition, structured around a creek meandering into a succession of mountain ranges that recede toward a distant waterfall almost exactly at center and then snowy caps on the horizon, is reminiscent of the classic formula inaugurated by Cole, except that the foreground is occupied not by the traditional rock and shrub but by a stream, muddy yet finely modeled and enhanced by delicate reflections. Along with this fine water texture, the subtle, softly sculptural treatment of light in differential hues of ochre aligns this picture with luminist tendencies. In mid-distance on the right side of the creek stand a group of tipis, some of their occupants highlighted by spots of bright red in their clothing, while to the left a small group of horsemen are in the process of crossing the water. This scene, whether based on actual observation during one of Whittredge’s trips—which, he wrote, impressed him with a sense of Arcadia—or constructed by his imagination, strikes us as nostalgic, even untimely.

The picture is contemporary with, yet apparently completely oblivious to, one of the most violent and most publicized moments in the long series of conflicts between the US government and Native American tribes in the second half of the nineteenth century, the Plains Wars, which culminated in the Battle of Little Big Horn in eastern Montana Territory in 1876. It is also out of line with contemporaneous imagery of the West delivered by press illustrations and survey photographs, which did not depict much Native American life, except in tightly controlled environments. Another landscape with figures, it references an ethnographic subject that, in spite of its realism, is more abstract and atemporal than Cooper and Cole’s Mohicans. Whittredge’s pastoral scene takes us out of history rather than into it, as it merges a Western setting and a Native American motif with the self-reflexive style of landscape art that had evolved and matured for fifty years in and around New York. Soon this style would decline, while Western and Native American motifs would rise in new configurations of landscape, associating ambitious painting with more popular imageries.

A century and a half later, as the very concept of landscape has been thoroughly redefined, particularly under the influences of environmentalist thought and Native or non-white re-appropriation efforts, this style of landscape art may appear obsolete. Yet the nostalgic appeal of the pastoral that already permeated the American paintings of the 1860s and 1870s lives on, as evidenced by countless images of contemporary culture from wall calendar photography to pseudo-“Indian” rituals. For this reason, among many others, it is worth looking again at the great achievement of nineteenth-century American painters who defied the incipient nostalgia of landscape painting as a genre and employed it instead to articulate their own questions about the many meanings of land in America.

-

See Albert Boime, The Magisterial Gaze: Manifest Destiny and American Landscape Painting, 1830-1965 (Washington, DC: Smithsonian Books, 1992) and Andrew Wilton and Tim Barringer, American Sublime: Landscape Painting in the United States, 1820-1880 (London: Tate Publishing, 2002). ↩︎

-

James P. Ronda, Finding the West: Explorations with Lewis and Clark (Albuquerque: UNM Press, 2006), 7. ↩︎

-

Thomas Jefferson, Notes of the State of Virginia (Boston: Lilly and Wait, 1832), 17. ↩︎

-

Peter John Brownlee, Manifest Destiny/Manifest Responsibility: Environmentalism and the Art of the American Landscape (Chicago: Terra Foundation for American Art, 2008), 13. ↩︎

-

Thomas Cole, “Essay on American Scenery,” American Monthly Magazine 1 (January 1836): 1-12. ↩︎

-

Diane Dillon, “Nature, Nurture, Nation: Appetites for Apples and Autumn during the Civil War,” in Peter J. Brownlee et al., Home Front: Daily Life in the Civil War North (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2013), 150-151. ↩︎

-

See the classic study by Angela Miller, The Empire of the Eye: Landscape Representation and American Cultural Politics, 1825-1875 (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1993). ↩︎