This was the era of impressionism, but unlike their French contemporaries, the American artists who practiced the “new art” were not initially part of a cohesive, identifiable group.1

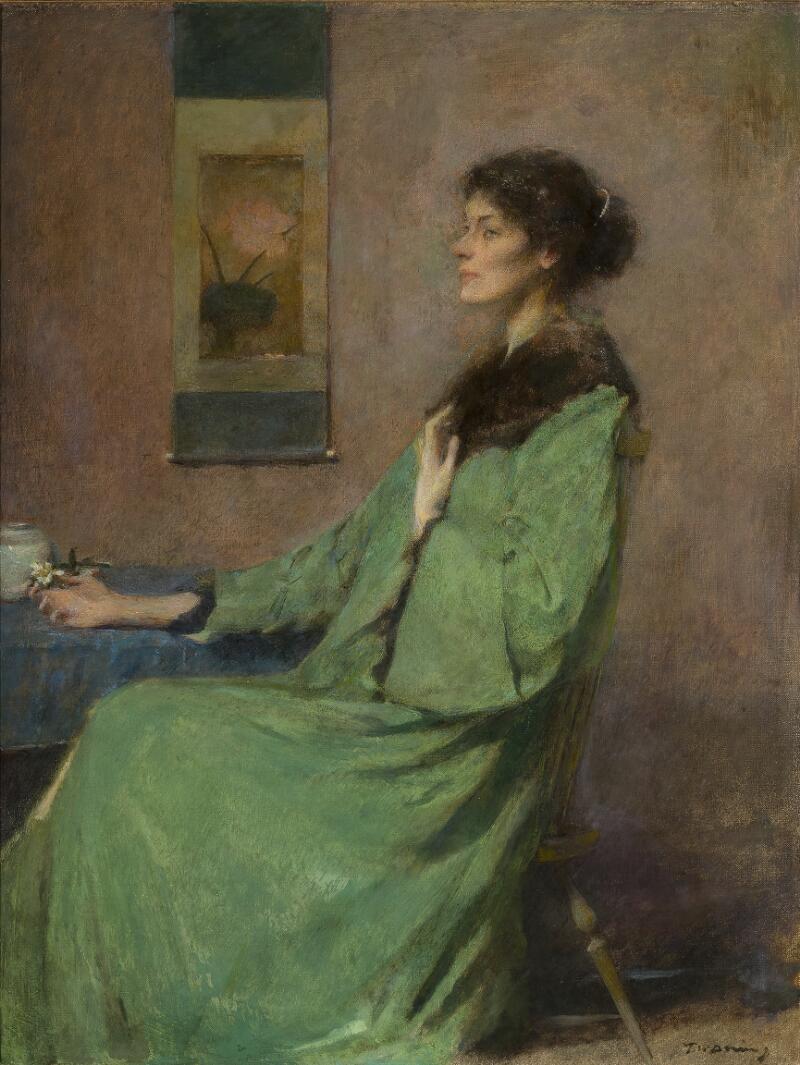

They rose to prominence in the late 1880s and 1890s, the period on which this essay will focus, but they did not join forces until 1898 when the Ten American Painters exhibited at Paul Durand-Ruel’s New York gallery. This collective, organized by the painters J. Alden Weir (1852–1919), John Henry Twachtman (1853–1902), and Childe Hassam (1859–1935), had defected from the Society of American Artists, which itself had been formed in protest against the conservatism of the National Academy of Design. The canvases they exhibited illustrated the varied nature of American painting of the so-called Gilded Age: while Frank W. Benson (1862–1951), Thomas Wilmer Dewing (1851–1938), and Edmund C. Tarbell (1862– 1938) leaned toward Whistlerian aestheticism, others such as Robert Reid (1862–1929), Hassam, and Twachtman embraced the brighter palette of impressionism and post-impressionism.2

Taken from an 1873 social satire by Mark Twain (1835–1910) and Charles Dudley Warner (1829–1900), the term “Gilded Age” has come to denote the period from the end of the American Civil War (1861–65) to the outbreak of the First World War (1914–1918).3 It was a time of rapid economic growth, technological expansion, and industrialization in America, especially in areas such as mining, iron and steel, shipping and railroads. There were dramatic social changes as well, with large numbers of people moving from the country to the city, increased immigration, a rising middle class, a new awareness of women’s rights, and the creation of superrich industrialists such as Cornelius Vanderbilt (1794–1877) and Andrew Carnegie (1835–1919).4 America was prosperous and confident, sophisticated and outward looking.

Bubbling beneath this prosperous veneer, however, was an undercurrent of corruption and social unrest—this period witnessed the assassination of three presidents: Abraham Lincoln, James Garfield, and William McKinley. In this materialistic, post-Darwinian world, economic exchange became the primary focus. In the artistic sphere, aesthetic worth might be viewed as less important than commercial value.5 Indeed, the second half of the nineteenth century saw the development of the modern art market in the United States, as well as in France, and the emergence not only of a new generation of collectors and middlemen—often artists—in cities such as Boston and New York, but of dealers such as Durand-Ruel, who brought impressionism to America in the 1880s.6

Gilded Age artists were united in their commitment to contemporary subjects, but to what extent did their work reflect the politics of their time, and its social and economic changes? Did they retreat to their summer havens and paint an idealized vision of America, far removed from contemporary reality—or did they succeed in creating a style of painting that reflected an evolving, modern nation? There is a tendency to dismiss American art of this period as picturesque and superficial, and its artists as derivative or second rank in relation to the French impressionists.7 My aim here is to dispel this myth through close analysis of six works from the Terra Foundation collection in relation to three broad themes: the relationship of style and influence between Claude Monet (1840–1926) and John Leslie Breck (1860–1899); the observation of social and technological change in paintings by Childe Hassam and William Merritt Chase (1849–1916); and modern women in the work of Edmund Tarbell and Mary Cassatt (1844–1926). As we shall see, American painting of this period was concerned not simply with, as one critic put it, “figures of gracious women and lovely children drenched in sweet sunlight,”8 but only if one is prepared to look beneath the surface.

In 1892 the Bostonian artist John Leslie Breck completed one of his most mysterious and evocative canvases, Morning Fog and Sun (Fig. 1).

John Leslie Breck (1860–1899)

Morning Fog and Sun, 1892

The scene is a meadow in Giverny in Normandy, where several grainstacks are viewed through a hazy morning light. The sun casts long, colored shadows across the golden fields, while a soft mist rises in the distance. Like primitive monoliths, the mounds of grain draw us toward the light; they are placed off-center, leaving a vast area of foreground and creating a dreamlike, meditative atmosphere. This is enhanced by short strokes of complementary colors, which blend at a distance—a technique close to the neoimpressionism of artists such as Georges Seurat (1859–1891) and Paul Signac (1863–1935).

The picture’s particular light effects and flattened, abstracted forms derive from one of the fifteen Studies of an Autumn Day (1891, Terra Foundation for American Art) that Breck completed the previous year.9 This small panel, painted entirely out of doors, evokes the blanching, almost blinding sensation of morning sunlight. But whereas the small studies were painted in the Giverny fields over the course of three days, the larger painting was completed over a much longer period, and most likely from memory after Breck had left France. Both the studies and the larger painting pay homage to Monet’s own series of grain stack paintings, which had enjoyed enormous commercial success at Durand-Ruel’s Paris gallery in 1891. The extent to which Monet influenced the direction of Breck’s work, however, deserves further exploration.

Since settling in Giverny in 1883, Monet had been exploring, and often struggling with, this motif, working on several canvases simultaneously and producing repeated images of one or two grain stacks viewed under different conditions of light and weather. Shortly after Breck paid his first visit to Giverny in 1887, Monet invited him to set up his easel in his garden, where the American began to experiment with broken brushwork and a brighter palette, producing a series of smallish canvases such as Garden at Giverny (In Monet’s Garden) (c. 1887–91, Terra Foundation for American Art).

It is worth comparing Morning Fog and Sun with Monet’s Haystack: Snow Effect (Fig. 2) in order to assess their intentions.

Claude Monet (1840-1926)

Haystacks: Snow Effect, 1891

Oil on canvas, 25 1/2 x 36 in. (65 x 92 cm). Scottish National Gallery, bequest of Sir Alexander Maitland, 1965, NG 2283

In both works, background detail is suppressed, creating an otherworldly, suggestive quality, close to symbolist art.10 The Edinburgh painting was included in the exhibition Van Gogh to Kandinsky: Symbolist Landscape in Europe 1880–1910, National Galleries of Scotland, Edinburgh, July 14, 2012-October 14, 2012. Yet Breck’s landscape is carefully painted and appears almost frozen in time, while Monet’s brushstrokes are expressive and gestural, and his application of paint more varied, contrasting warm, sunlit areas with cooler blues and violets. Despite its apparent modernism, Breck’s picture reflects his academic training, which had taught him to work toward carefully finished, large-scale works such as his Autumn, Giverny (The New Moon) (1889, Terra Foundation for American Art). This canvas has a similarly suggestive, neosymbolist undertone, which finds its source in the romanticism of Jean-François Millet (1814–1875), rather than Monet.

Breck’s studies also differ from Monet’s 1891 paintings in tone and technique. Monet painted quickly in order to express instantaneity—the transience of the moment—and, as he wrote, “above all the enveloppe, the same light diffused over everything,”11 Breck was interested in carefully and prosaically recording the passage of the sun across the sky over the course of a day; he was responding, in his own way, to an aspect of the Giverny landscape that was painted by numerous members of the art colony there, among them Willard Metcalf (1858– 1925), Theodore Wendel (1859–1932), Theodore Robinson (1852–1896), and Lilla Cabot Perry (1848–1933). Breck may have observed Monet closely and absorbed certain aspects of impressionist theory, but with Morning Fog and Sun he was working toward an altogether more aesthetic and atmospheric end, intended for an American, rather than a French, audience.

In 1899 the picture was exhibited at the artist’s memorial exhibition at the St. Botolph Club in Boston as Haystacks at Giverny, thus drawing attention to Monet and the village associated with his famous grain stacks series.12 Breck’s close relationship with the leader of impressionism was further underlined in the foreword to the exhibition catalogue, which noted that Monet had “distinguished Breck by appreciation and encouragement and afforded him unusual opportunities to paint with him in the fields.”13 More recently, art historians such as Derrick Cartwright have exaggerated this relationship, writing that “painters like Breck did not simply live in the village, they imitated Monet’s technique and took on his favorite subjects.”14 In reality, neither Breck nor any of the other artists at Giverny were attempting to “imitate” the French master; on the contrary, they forged their own independent paths, while practicing a hybrid style of painting that combined differing tendencies, from naturalism to neoimpressionism.

Like Breck, fellow Bostonian Childe Hassam practiced an eclectic style that drew progressively on naturalism, impressionism, and postimpressionism. He always maintained that his most important influence was the Dutch artist Johan Barthold Jongkind (1819–1891), from whom he learned to lighten his palette, even before moving to France in 1886. While Breck was working near Monet at Giverny, Hassam was in Paris, preoccupied with his submission to the Paris Salon of 1887, Une Averse—rue Bonaparte (Fig. 3).

Childe Hassam (1859–1935)

Une Averse—rue Bonaparte, 1887

Painting in a naturalist style suitable for an official exhibition, Hassam nevertheless chose a contemporary urban subject—a corner of the city not far from the Luxembourg Garden, the periphery of which is just visible in the distance. The archetypal flâneur, he turned his back on the obvious tourist view—the magnificent façade of the church of St. Sulpice—and surveyed instead the full extent of the rain-soaked rue Bonaparte, with hansom cabs lined up along the wall of the seminary to the left, and hurrying pedestrians sheltering under black umbrellas on the right. The view recalls the artist’s first essay as the “painter of streets,” Rainy Day, Boston (1885, Toledo Museum of Art, Ohio).

As curator David Park Curry has noted, Hassam was interested in urban change, which he encountered all around him both in Boston and Paris.15 In his view of the rue Bonaparte he further observes the disparity between rich and poor. The critic Theodore Child (1846–1892) compared Hassam to Giuseppe de Nittis (1846–1884), who painted the Parisian bourgeoisie,16 but the addition of the peddler and his daughter brings him more in line with the social realism of French artist Jean-François Raffaëlli (1850–1924). Hassam uses these figures as a contrast to what he described as the “more fortunate wayfarers with umbrellas” and the cabdrivers, who are “better dressed.”17

The Boston critic Susan Hale (1833–1910) made special note of “the high blank wall covered in posters of all tints.”18 Close observation reveals that at the top of the cab rank, to the right of the seminary door, is Jules Chéret’s color lithograph for Alexandre Dumas’s popular 1844 novel Les Trois Mousquetaires (The Three Musketeers), cleverly juxtaposed with three cab drivers standing underneath. To the left of the door, another poster announces an event in aid of “Les Inondés du Midi” (the flood victims of the Midi), perhaps a discreet reference to the rain-filled scene before us, but also a reminder of the severe flooding across the Var region of France in December 1886. Among the state-funded events organized in aid of the victims was an exhibition at the École des Beaux-Arts, 14 rue Bonaparte—that is, the other end of the same street.19

While Une Averse—rue Bonaparte is set in a historic part of Paris and is painted in a conventional naturalist style, it is nevertheless full of contemporary social detail. Hassam’s Commonwealth Avenue, Boston (Fig. 4) is almost the opposite: situated in one of Boston’s newest streets, it is painted with the light palette and fragmented brushstrokes of impressionism, yet was executed in New York, largely from memory, and is full of subtle historic references.

Childe Hassam (1859-1935)

Commonwealth Avenue, Boston, c. 1892

The view looks northeast toward the public garden adjacent to Boston Common, where a memorial to the American Civil War is just visible, while on the right the solid neo-Romanesque tower of the First Baptist Church, designed by Henry Hobson Richardson (1838–1886), has a position of prominence. This congregation had an important history in American race relations: it had welcomed nonwhite members from as early as 1772, ordained the first African-American pastor in Boston, and in 1889 began a Chinese Sunday school. Its new building, completed in 1871, was famous for its distinctive friezes, designed by the French sculptor Frédéric Auguste Bartholdi (1834–1904), best known for creating the Statue of Liberty. These included the likenesses of both President Abraham Lincoln (1809–1865) and Charles Sumner (1811–1874), leader of the antislavery movement in Massachusetts. These heroes look down on what was, in 1892, one of the most fashionable streets in Boston, indicated by the elegant town houses, carriages, and the promenading figures, there simply to be seen.

Hassam’s painting also celebrates modern urban design, since Commonwealth Avenue was the first residential area of its kind to be built in America. The district, known as Back Bay, was developed on landfill in what had once been a marshy wasteland, and the street was constructed between 1861 and 1899, designed by the Boston architect Arthur Delevan Gilman (1821–1882).20 The elegant townhouses, soon to be inhabited by the wealthy mercantile classes, were laid out on either side of a broad avenue, 240 feet wide, which was equipped with shady, tree-lined walkways, designed to promote health and well-being, and inspired by Baron Haussmann’s transformation of Paris in the 1860s.21 On the left of the composition the figures of a promenading woman and child signal to the viewer that this is now a safe, sanitized, and genteel area.

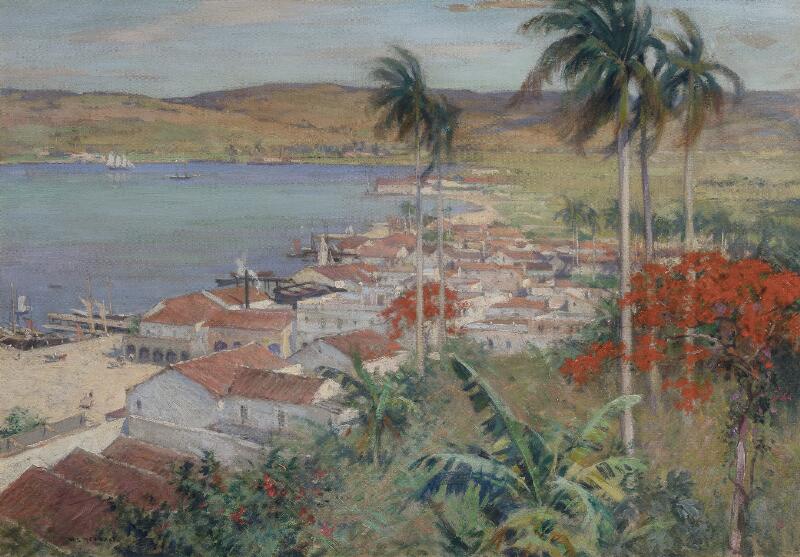

We find the same juxtaposition of bourgeois leisure and modern design in William Merritt Chase’s Morning at Breakwater, Shinnecock (Fig. 5).22

William Merritt Chase (1849–1916)

Morning at Breakwater, Shinnecock, c. 1897

Shinnecock is an area on the South Fork of Long Island where in 1891 Chase was appointed by the art patron Janet Hoyt (1847–1925) to direct a new art school dedicated to plein-air painting. After the extension of the railroad from New York City to Sag Harbor in 1872, tourist resorts had begun to spring up all along the South Fork’s southern shore. The painting shows a group of women and children—possibly including Chase’s own family—playing on the beach at Shinnecock Bay, close to Chase’s summer house, designed by his friend Stanford White (1853–1906) in 1892.23

Chase draws attention to the large man-made structures on the left: the breakwaters.24 These not only guide us into the composition but offer a strong, masculine counterpoint to the soft, hastily sketched forms of the women and children on the right. Two breakwaters are visible, constructed from large pieces of granite, kept in place by long wooden buffers. The bay’s original channel to the Atlantic Ocean had silted up, and its water had become brackish and unsanitary; the breakwaters were part of an engineering project to reconnect Shinnecock to the ocean through a canal, completed in 1892.25 Designed to prevent further movement of sand and to control the force of the waves, the breakwaters also created a sheltered area suitable for bathing. Chase shows no sign of anyone entering the water, suggesting that the water was still unsuitable for swimming.

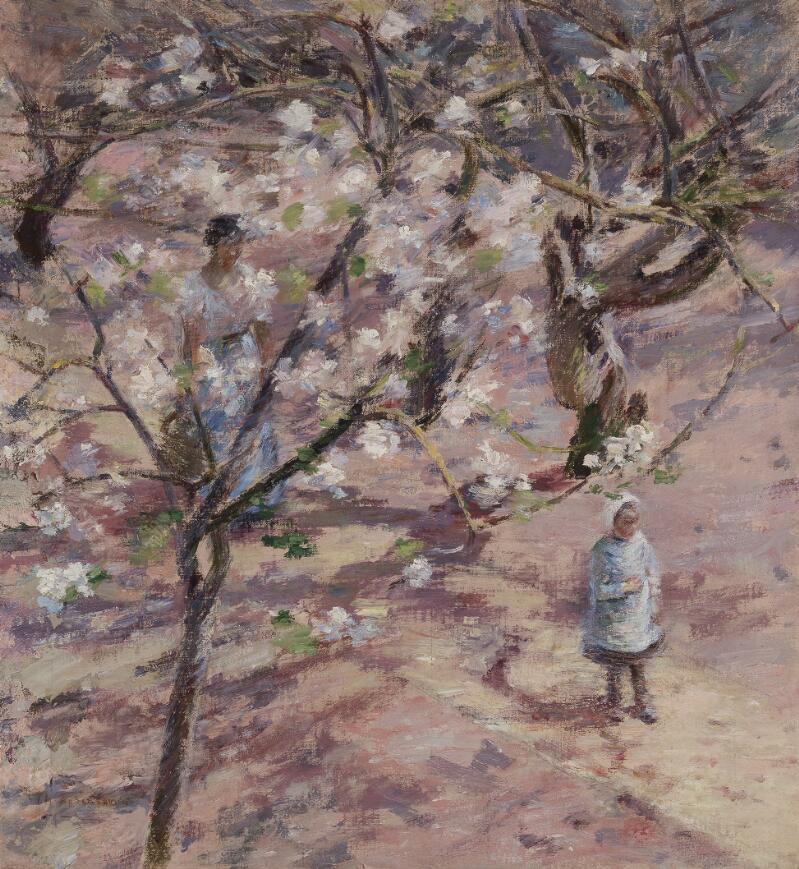

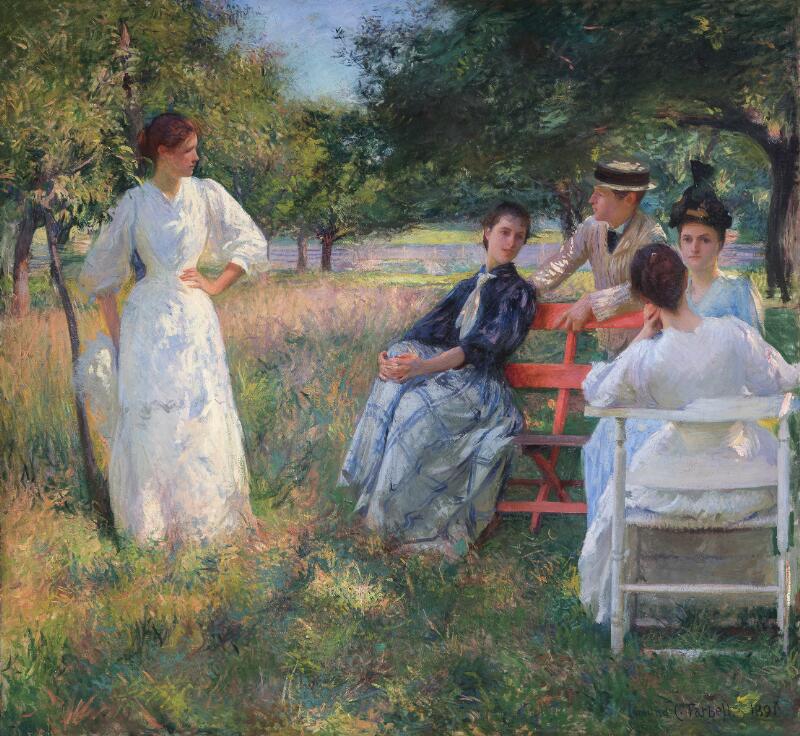

The father of six daughters, Chase was supportive of his female students, declaring, “Genius has no sex.”26 The Massachusetts painter Edmund Tarbell, too, was surrounded by powerful women, as exemplified by his masterpiece, In the Orchard (Fig. 6), which shows family and friends relaxing in the French countryside.

Edmund C. Tarbell (1862–1938)

In the Orchard, 1891

The self-assured woman on the left, with hand on hip, is the artist’s sister-in-law, Lydia Souther Hatch. Seated opposite her is Lemira Eastman, a family friend, looking equally modern in her fashionable yet practical “rational” dress. On the far right, Tarbell’s wife, Emeline, herself a trained artist, confronts the viewer with a direct gaze.

When the painting was exhibited at the New York Academy in 1892, a critic for the New York Times noted that the women were “of that sturdy type of girlhood often seen in Massachusetts; their ruddy cheeks, the coarse paint on the bench, the colors of the sky and grass … all very positive in hue.”27 One can detect a note of disapproval in the writing; to this critic, the painting’s bright palette and lack of finish and finesse were a reflection of its somewhat brazen subjects. The Times preferred the Whistlerian elegance of Frank Benson’s By the Firelight (1889, private collection), which portrayed a slender young woman in black evening dress, bathed in the soft, reflected glow of a fire. Tarbell’s painting, by contrast, was decidedly contemporary and executed in the new, broadly impressionist style, even making tacit reference to Renoir’s Luncheon of the Boating Party (1880–81, Phillips Collection, Washington, DC).

Though the painting’s style and location was French, its subject was, as another critic of the time noted, “purely American,” reflecting a nation that was, like these New England women, self-assured and outward looking.28 The same confidence and optimism infuses images such as Benson’s Summer (1909, Museum of Art, Rhode Island School of Design, Providence). Here, a group of young women, hatless and bathed in sunshine, occupy themselves in the open air, while the artist’s daughter Eleanor stands proudly erect, hand on hip, surveying the vast world that lies before her.

In 1892, the year after Tarbell produced In the Orchard, Mary Cassatt began working on her mural decoration for the central court of the Woman’s Building of the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago. She had been commissioned to paint an allegory of “Modern Woman” (Fig. 7) as a foil to Mary MacMonnies’s panel devoted to “Primitive Woman.”29 Cassatt, like Tarbell, chose to place her modern women in an orchard, but instead of conversing they are, according to Cassatt, “plucking the fruits of knowledge or science.”30

Mary Cassatt (1845-1926)

Modern Woman, 1893

Published in color in William Walton, World’s Columbian Exposition 1893: Art and Architecture, Vol. 1 (Philadelphia: George Barrie, 1893). Ryerson and Burnham Libraries, Art Institute of Chicago

Tarbell gives us women of leisure, while Cassatt offers active, working women, eager to improve their minds. On the other hand, while Tarbell’s models are dressed in the latest rational wear, Cassatt’s are dressed in decorative but impractical gowns fashioned from delicate fabrics such as silk and taffeta.

The following year Cassatt acquired her first property, the Château de Beaufresne, in the Oise region not far from Paris. Here, seated on the edge of a pond, she painted Summertime (Fig. 8), arranging her models to give the impression of a young girl and her older companion enjoying a boat ride. The woman is dressed in a cool pink long-sleeved dress and, unlike the women in Tarbell’s and Benson’s paintings, she wears a wide-brimmed hat and white fabric gloves—clothes designed to maintain a pale complexion.

Mary Cassatt (1844–1926)

Summertime, 1894

By contrast, the girl has only her hat to shield her from the sun. She is bare-shouldered and the strap of her skimpy white sundress has fallen down. There is no hint of eroticism, but the juxtaposition is deliberate and the inference drawn depends on the viewpoint of the spectator. A mother might criticize the woman for neglecting to protect her young charge from sunburn; while a nineteenth-century feminist might envy the younger girl’s freedom: she is enjoying the summertime of life and is not yet obliged to follow the restrictive dress code imposed by adult society.

Like the women in Cassatt’s mural, the models in Summertime seem also to be thirsting for knowledge, looking down into the water with empirical curiosity.31 The cropping of the boat on the right hand side suggests the presence—or rather absence—of a male rower or punter: the women are free to float across the water, contemplating nature. Curator Judith Barter has compared the meditative quality of Cassatt’s images of women and children in boats with the Asian concept of life as a voyage down an “ever-changing river.”32 Cassatt collected Japanese prints and had been inspired by the 1890 exhibition of Japanese art at the École des Beaux-Arts, encouraging her to experiment with the unusual viewpoint and flattened space evident in Summertime.33 Cassatt may also have been aware of Monet’s paintings of his stepdaughters boating at Giverny, which adopt a similarly high viewpoint. On the whole, however, Cassatt, like Breck and the other American artists of their generation, distanced herself from Monet’s impressionism, preferring, like Degas, to define herself as an independent artist.

Like their French contemporaries, Cassatt and her peers were aware of the social and economic changes around them, both in France and America, and this awareness is reflected in the figurative paintings of Tarbell and Cassatt as much as in the landscapes of Hassam and Chase. As these examples from the Terra Foundation reveal, American painting of this period was not restricted to elegant women in white dresses bathed in sunlight; beneath its charming surfaces lay a complex world of social, historical, and technological change. In order to reflect this evolving modern landscape, artists adopted and adapted a variety of new approaches and techniques: the immediacy of realism, the broken brushwork of impressionism, the decorative qualities of tonalism and japonisme and even the prismatic palette of neoimpressionism. In the end, they developed a fusion of styles that epitomized the richness and diversity of America’s Gilded Age.

-

On American impressionists see William H. Gerdts, American Impressionism (New York: Abbeville Press, 1984); Kathleen Adler, Erica E. Hirshler, and H. Barbara Weinberg, American Artists in Paris 1860–1900 (London: National Gallery, 2006); and Katherine M. Bourguignon, ed., American Impressionism: A New Vision 1880–1910 (Paris: Hazan, 2014). ↩︎

-

The remaining three artists in that group were Joseph R. DeCamp (1858–1923), Edward Simmons (1852–1931), and Willard Leroy Metcalf (1858–1925). On aesthetics and impressionism in Gilded Age painting see Sarah Burns and John Davis, eds., American Art to 1900: A Documentary History (Oakland: University of California Press, 2009), 941–1013. ↩︎

-

Mark Twain and Charles Dudley Warner, The Gilded Age: A Tale of Today (Hartford: American Publishing Company, 1873). ↩︎

-

On this period in New York, see Esther Crain, The Gilded Age in New York, 1870–1910 (New York: Black Dog & Leventhal, 2016). ↩︎

-

In 1888 the critic Sheridan Ford published a pamphlet, Art: A Commodity, exposing bad practices in the art market. ↩︎

-

See Jennifer A. Thompson, “Durand-Ruel and America,” in Inventing Impressionism: Paul Durand-Ruel and the Modern Art Market (London: National Gallery, 2015), 134–151. On the market for impressionism in Boston see Erica E. Hirshler, Impressionism Abroad: Boston and French Painting (London: Royal Academy of Arts, 2005), 17–39. ↩︎

-

See, for example, the press response to the 2014 exhibition American Impressionism: A New Vision 1880–1910, National Galleries of Scotland, Edinburgh. ↩︎

-

William Howe Downes, “The Spontaneous Gaiety of Frank W. Benson’s Work,” Arts and Decoration 1 (March 1911): 195, cited in Hirshler, Impressionism Abroad, 35. ↩︎

-

See John Leslie Breck, Studies of an Autumn Day, 1891. Oil on canvas, 12 7/8 × 16 1/16 in. (32.7 × 40.8 cm). Terra Foundation for American Art, Daniel J. Terra Collection, 1989.4.3. ↩︎

-

The Edinburgh painting was included in the exhibition Van Gogh to Kandinsky: Symbolist Landscape in Europe 1880–1910, National Galleries of Scotland, Edinburgh, July 14, 2012-October 14, 2012. ↩︎

-

Monet in a letter to Gustave Geffroy, 1890, cited in John House, Monet: Nature into Art (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1986), 198. ↩︎

-

As Nina Lubbren has pointed out, after the success of Monet’s grain stack series, the haystack, a familiar aspect of the cycle of the seasons, visible in most European agrarian landscapes, became intimately associated with Giverny as part of a “place-myth.” Katherine M. Bourguignon, ed., Impressionist Giverny: A Colony of Artists, 1885–1915 (Chicago: Musée d’Art Américain, Giverny/Terra Foundation for American Art, 2007), 36. ↩︎

-

Foreword, 1899 Memorial Exhibition of Paintings by John Leslie Breck (Boston: St. Botolph Club, 1899). ↩︎

-

Derrick R. Cartwright, The City and the Country: American Perspectives 1870–1920 (Chicago: Musée d’Art Américain, Giverny/Terra Foundation for American Art, 1999), 18. ↩︎

-

David Park Curry, Childe Hassam: An Island Garden Revisited (New York: W. W. Norton, 1990), 134. ↩︎

-

Theodore Child, “The Paris Salon of 1887,” The Art Amateur 6, no. 6 (May 1887): 126. ↩︎

-

Cited in H. Barbara Weinberg, Childe Hassam: American Impressionist (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2004), 61. ↩︎

-

Susan Hale, Boston Transcript 1887, Archives of American Art, [1993.20], Roll NAA1, Frame 489. ↩︎

-

Patrice Havard, “Hier, aujourd-hui … mais demain?” in Sapeurs-Pompiers de France, no. 1093 (October 2016): 67. ↩︎

-

Raymond H. Robinson, “The Families of Commonwealth Avenue,” Proceedings of the Massachusetts Historical Society, Third Series, 93 (1981): 80. ↩︎

-

On Haussmann and the “greening” of Paris, see Clare A. P. Willsdon, “Promenades et plantations: impressionism, conservation and Haussmann’s reinvention of Paris” in F. Fowle and R. Thomson, eds., Soil and Stone: Impressionism, Urbanism, Environment (Aldershot, UK: Ashgate, 2003), 107–124. ↩︎

-

Art historian William Gerdts has suggested that Chase was encouraged to paint such a contemporary subject by his good friend Alfred Stevens (1823–1906), whose scenes of the Normandy coast may have been an initial source of inspiration. Even closer to the spirit of Chase’s painting, however, are Eugène Boudin’s (1824– 1898) 1890s paintings of holidaymakers at Deauville and Trouville, which take in the vast expanse of sky and beach and employ the same pale, luminous tonality or “peinture claire.” See William H. Gerdts, Lasting Impressions: American Painters in France 1865–1915 (Chicago: Musée d’Art Américain, Giverny/Terra Foundation for American Art, 1992), 76, and John House, Impressionists by the Sea (London: Royal Academy of Arts, 2007), 136. ↩︎

-

White was also commissioned to build the club house for the Shinnecock Hills golf club, established the previous year. ↩︎

-

Chase painted a more focused version of the breakwater in The Lone Fisherman, oil on panel, 15 × 11 7/8 in. (38.1 × 30.2 cm), Hood Museum of Art, Dartmouth College, P.940.40. ↩︎

-

The canal created a link with Peconic Bay. In 1896, shortly before Chase produced this work, a further channel was excavated in an attempt to create a link to the Atlantic Ocean, but the attempt failed. See Nobel E. Whitford, History of the Canal System of the State of New York, vol. 1, chap. 12 (New York, 1905), accessed on 1 June 2017. ↩︎

-

Cited in Erica Hirshler, “Old Masters Meet Modern Women,” in Elsa Smithgall et al., William Merritt Chase: A Modern Master (Washington, DC: Phillips Collection, 2016), 25. ↩︎

-

Anonymous critic, “Academy Sculpture and Painting,” New York Times, 5 April 1892. ↩︎

-

“The Fine Arts at the National Academy’s Spring Exhibition,” The Independent, April 14, 1892, 11. ↩︎

-

On this project see Judith A. Barter, Mary Cassatt: Modern Woman (New York: Harry N. Abrams, 1998). ↩︎

-

Cassatt to Bertha Palmer, 11 Oct 1892 in Nancy Mowll Mathews, Cassatt and Her Circle: Selected Letters (New York: Abbeville Press, 1984), 238, cited ibid., 88. ↩︎

-

Clare A.P. Willsdon, Impressionist Gardens (Edinburgh, National Galleries of Scotland, 2010), 155. ↩︎

-

Barter, Mary Cassatt, 86. ↩︎

-

The Terra painting is noticeably more focused than the second version of Summertime (about 1894) in the Armand Hammer Foundation, Carpinteria, California. ↩︎