Introduction

Archibald J. Motley, Jr. (1891–1981)

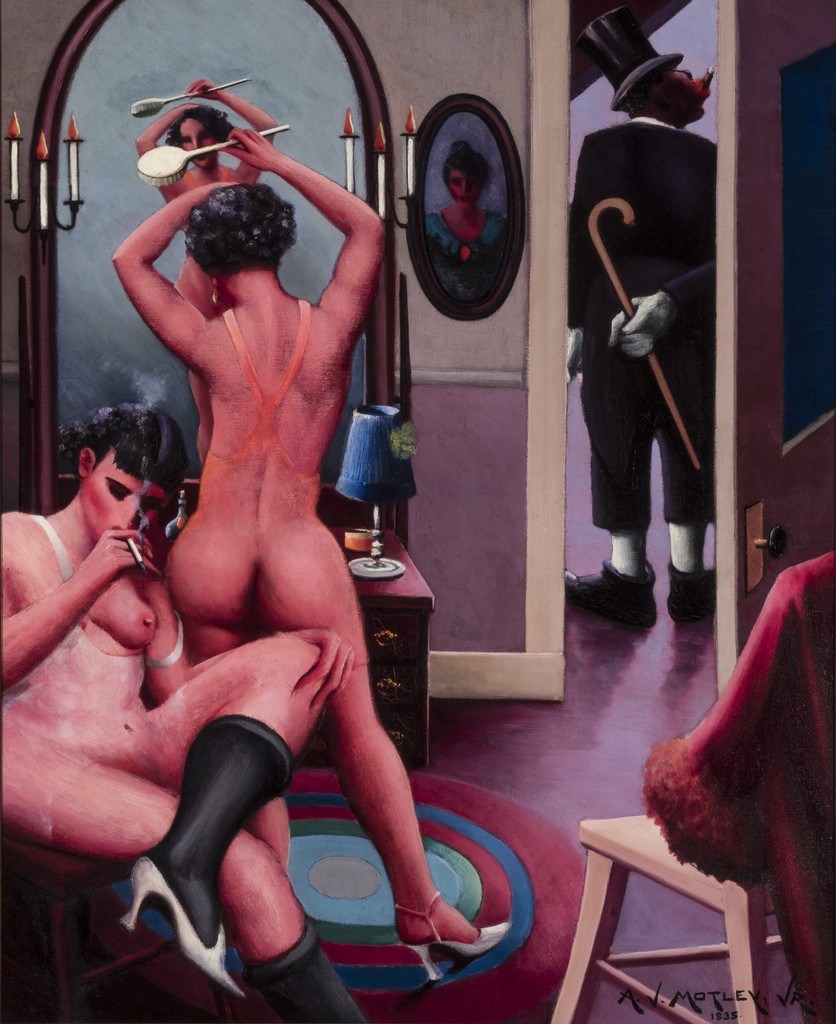

Between Acts, 1935

Archibald J. Motley Jr., one of the best-known African American artists of the twentieth century, broke new ground by depicting contemporary black urban subjects in portraits and images of everyday life. Working mainly in Chicago, he painted lively South Side street scenes with brilliant colors, dramatic light effects, and stylized forms evocative of jazz and the blues. Between Acts makes the observer a backstage voyeur, peering into a dressing room where two nearly naked female performers relax. A top-hatted figure stands just outside the door, holding a cane behind his back and smoking a cigar. His clownishly oversized hands and exaggerated red lips refer unmistakably to the racist caricatures of blackface minstrel shows, which drew audiences well into the twentieth century. Motley’s use of streamlined, stylized forms and eccentric color schemes endow such images with a fantastical quality.

Learn more about this painting on the Terra Foundation website.

Perspective

When philosopher and critic Alain Locke wrote in 1936 that, in contrast to the artistic sobriety of many African American painters and sculptors, “[Archibald] Motley’s Rabelaisian turn is a promising departure,”1 he probably had in mind a painting like Between Acts (1935). Part of Motley’s (1891–1981) exploration of Chicago’s predominately African American, culturally vibrant, status-conscious Bronzeville neighborhood, Between Acts portrays one of that community’s more sordid aspects: the scantily clad showgirls and ludicrous blackface comedians who performed in local theaters and night- clubs. Instead of depicting these entertainers dancing and clowning, Between Acts shows them offstage, and, in essence, out of their respective, invented characters—smoking, idling, and primping before a mirror.

In typical Motley fashion, Between Acts used an intimate, boudoir-like setting as a rationale for painting naked and virtually nude women in seductive poses, a strategy he also employed in Brown Girl After the Bath (1931, Columbus Museum of Art, Ohio) and Black Belt (1934, Hampton University Museum, Virginia). Like the paintings of George Grosz (1893–1959), with their depictions of the moral decay of Weimar Berlin, Between Acts suggests a narrative with moral overtones about denizens of the African American demimonde forming their own confraternity (or in this instance, a consorority) of social outsiders. As targets of spectatorship and derision, these two “loose women,” and the stereotypical black jokester standing in the doorway, performed their desultory roles against the social backdrop of moral probity and racial uplift. And yet by painting them as a trio of sorts—in a casual, nontheatrical way—and within a composition of arches, rectangles, and interior patterns, Motley challenged Bronzeville’s more somber and neurotic side via an audacious, transgressive scene of explicit female sexuality and hyperbolic blackness.

Three iconographic flashpoints in Between Acts—the blackface minstrel’s cane, the painted portrait of a woman on the dressing room wall, and the seated woman’s crossed leg sporting black hosiery and a white “Spanish heel” shoe—insert subliminal content that, given their somewhat Freudian, psycho-sexual connotations, may explain the painting’s forty-odd year confinement to Motley’s studio. The painted oval portrait aligns with the depicted room’s wall and creates a link between the two women on the left and the man on the right; it contributes to the enigmatic nature of Between Acts a shadowy, intractable cameo of a sitter whose vague identity echoes the elusive and problematic personae of the flanking minstrel and showgirls. Motley’s fearless probing of the psychological symbolism of figural subjects and compositional elements set him apart from other Depression-era artists (and likewise from a conservative American art market) and, in matters pertaining to racial identity and sexual mores, singularized his work.

“Motley seems more and more fascinated by the grotesqueries and oddities of Negro life,” Locke astutely noted, “which he sometimes sarcastically, sometimes sympathetically, depicts.”2 In the case of Between Acts, one might add to Locke’s assessment Motley’s at times problematical, insurrectionary depictions: pictorial passages that introduced impolitic issues the majority of Americans preferred to sweep under society’s metaphorical carpet.