Introduction

Walter Ufer (1876–1936)

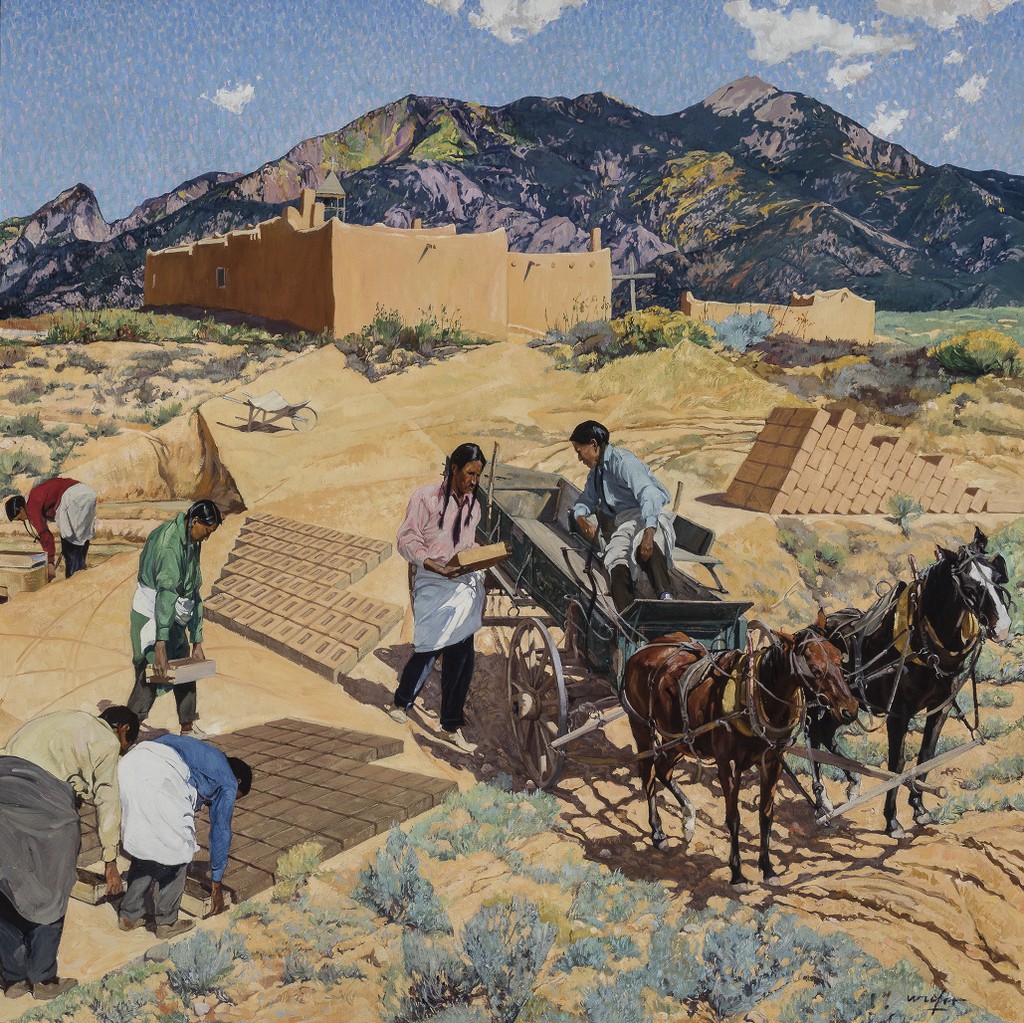

Builders of the Desert, 1923

In the early twentieth century, Walter Ufer, a leading member of the Taos art colony, became well known for his naturalistic depictions of New Mexico and its indigenous inhabitants. Builders of the Desert shows several stages of adobe brick construction while rendering the unique effects of the glaring sun on the region’s parched landscape. It demonstrates Ufer’s adherence to plein-air painting and his remarkable ability to transcribe New Mexico’s unique colors. It also delivers a strong social message. The rugged mountains and vertical lines of the adobe church contrast sharply with the hunched postures of the Taos Puebloans. By highlighting the backbreaking labor necessary to produce such buildings, Ufer vividly portrays contemporary Pueblo life in ways that refute the romantic stereotype of the so-called vanishing race.

Learn more about this painting on the Terra Foundation website.

Perspective

Walter Ufer’s 1923 painting Builders of the Desert exemplifies the Taos Society of Artists’ potent blend of academic proficiency and identifiably American subject matter. Though Ufer, like many of the group’s members and patrons (including the well-known manufacturer Oscar Mayer [1859–1955]), was of German ancestry, he supported the United States’ involvement in World War I, lending his skills as an illustrator to the government’s Fourth Liberty Loan war bond poster campaign. His “Guard Your Interests,” “For Freedom of the Seas,” and “Bomb The Hun!” designs encouraged anti-German wartime sentiment.

Prior to 1917, American artists still favored studies abroad. Ufer, aspiring to move beyond commercial art, returned to his native Germany in 1911 to study painting and to visit European collections. Following the example of his Munich teacher, Walter Thor (1870–1929), whose technique encouraged painterly immediacy in rendering color through light and shadow, Ufer produced remarkable portraits of rural types such as Tyrolean Woman—Plein Air (1912, collection of Mike Abraham).

Ufer returned to Chicago ready to transfer his skills to an American context, and the city’s mayor, Carter Harrison Jr., garnered support among the city’s sizable German-American business community to send the artist to New Mexico in 1914. The former territory had become the nation’s forty-seventh state two years prior, just over 60 years after Mexico ceded its holdings in the American Southwest following the Mexican–American War (1846–48). Taos and Santa Fe quickly emerged as destinations for artists, writers, and collectors inspired by the Santa Fe Railway’s promotion of New Mexico’s clear skies, Pueblo architecture, and the topographic splendor of plains, mountains, basins, mesas, and desert. The Taos Society of Artists was subsequently founded in 1915 and its members earned national acclaim for their distinctive American landscapes. Travel postcards promoted art as “A Taos industry”: one iconic image shows a painting palette inset with regional landscape; another shows an artist (looking remarkably like Ufer in his signature Stetson cowboy hat) outdoors at his easel.

In 1918 Ufer was already being described as “the strongest painter” of the Taos group.1 Builders of the Desert, labeled a “fine landscape” in 1924,2 ambitiously combines multiple images of Taos Puebloans—all of whom resemble Ufer’s friend and model Jim Mirabal—engaged in various stages of traditional adobe-building practice. Pueblo Peak, seen in the distance, and the ruins of the original San Geronimo church rising in the middle ground identify the geographic location under a bright midday sun.

Ufer’s painting attests to the hard-won survival of Pueblo culture in the twentieth century. In 1921 the federal Office of Indian Affairs issued Circular No. 1665 classifying certain dances and rituals as “Indian Offences”; in 1923—the year Ufer’s picture was painted—a supplement to the circular further refined this condemnation.3 The 1922 Bursum Bill aimed to reduce native land ownership through federal regulation.4 These efforts failed and today the Tiwa-speaking community of Taos remains a “living Native American community,” a UNESCO-designated World Heritage Site, and a National Historic Landmark.5

-

“Artist’s Corner,” Taos Valley News, Febru- ary 26, 1918, Chicago Times, as quoted by Dean A. Porter in “A Biography of Walter Ufer,” in A Place in the Sun: The Southwest Paintings of Walter Ufer and E. Martin Hennings (Norman, OK: University of Oklahoma Press, 2016), 35. ↩︎

-

E.L., “Some Prize Winners in the Pennsylvania Academy Annual Exhibition,” The Art News 22, no. 18 (February 9, 1924): 2. ↩︎

-

See Circular No. 1665. ↩︎

-

See American Indian Defense Association and Matthew Martinez, “All Indian Pueblo Council and the Bursum Bill”. ↩︎

-

See Taos.org and UNESCO World Heritage List, “Taos Pueblo”. ↩︎