Introduction

Edward Hopper (1882–1967)

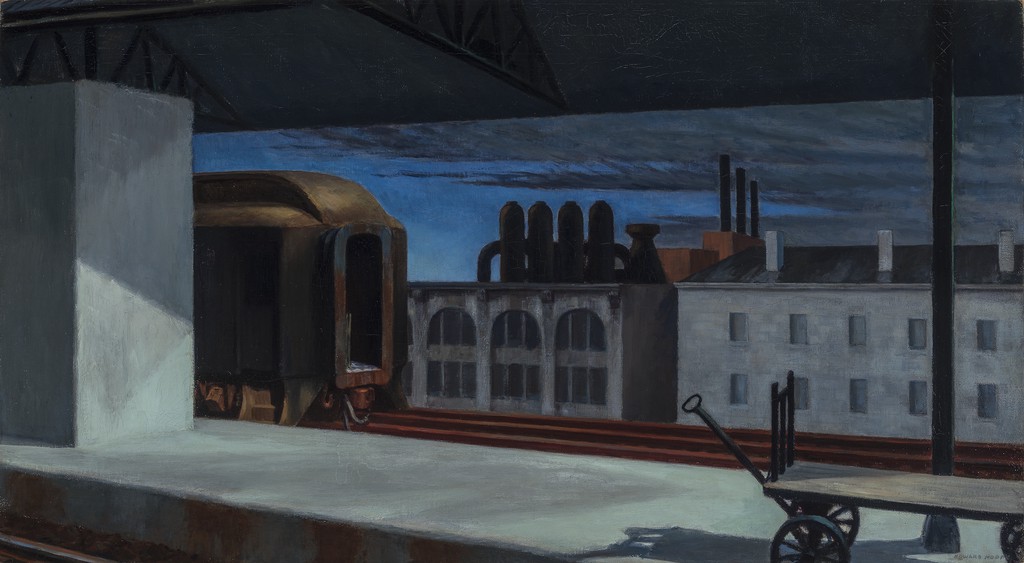

Dawn in Pennsylvania, 1942

Edward Hopper, one of the twentieth century’s most significant artists, produced seemingly mundane yet mysterious and disquieting images of American life. Throughout his career, his compositional style and emphasis on architectural structures over human figures distinguished him from his contemporaries. Dawn in Pennsylvania is a haunting vision of a deserted railroad station platform seen from across railroad tracks. In the background, a row of industrial buildings anchors the picture. The back end of the static train car underscores the stillness of the scene while conflicting light sources, suggestive of both dawn and sunset, reinforce its eeriness. With its broad horizontal format, dramatic contrasts of light and shadow, and illusionistic framing of a central depth bound by flat façades, the painting evokes a theatrical stage on which a narrative is about to begin. Even the vacant railroad platform hints at the rootlessness and anonymity of modern life.

Learn more about this painting on the Terra Foundation website.

Perspective

The meaning and importance of Dawn in Pennsylvania do not derive solely from Edward Hopper’s treatment of an almost empty railway platform with industrial buildings in the background, or from the painting’s clichéd atmosphere of silence and solitude. The image thwarts any attempt at a convincing, visually justified narrative. It is remarkable because while maintaining its individual character it brings into focus the most interesting aspects of Hopper’s oeuvre as a whole.

In terms of structure, the picture evinces his proclivity for multiplying frames: the frame of the painting is internally doubled by the lines of the platform, its roof, massive pillar, and post on the right. The result is a special role assigned to the platform, no longer a “non-place,” to borrow the term coined by anthropologist Marc Augé, but a pictorial stage for viewing and—only potentially—approaching the cinema-screen-like image formed by the gloomy cityscape set against the dawning sky in the painting’s background. The main “actors” that connect the platform/stage and the cityscape backdrop are the lug- gage cart to the right and the train car, which together also perform the role of stage “curtain.” Neither element dominates—they maintain a productive, balanced tension between stasis and action, between the whole and the fragment, reminding viewers of the photographic and cinematic qualities of Hopper’s work.

The fragmentary nature of the train stresses a quasi-photographic fixity, while also implying movement out of the frame at left and the vehicle’s imminent disappearance. Moreover, as much as one wishes to recognize the familiar scene of a departing train, its almost perfectly symmetrical relation to the cart on the right perceptually holds it in its place. This tension between what film critic and theorist André Bazin (1918–1958) called the centrifugal cinematic screen and the centripetal logic of painting, along with the photographic effect of a freeze- frame, exemplifies the close connection of Hopper’s painting with other media.

The uncanny aspect of Dawn in Pennsylvania is a combination of its internal coherence and external orientation, the degree to which it is haunted by traces of other Hopper works. First of all, the nocturnal Nighthawks (1942, Art Institute of Chicago) serves as a structural template for the overall composition of Dawn in Pennsylvania, including the wedge-shaped internal framing and the almost identical vertical element on the right. Dawn in Pennsylvania also connects to other railroad paintings by Hopper: like Railroad Train (1908, Addison Gallery of American Art, Andover, Massachusetts) it employs a fragmentary rendition of the main motif and a diagonal orientation; and its platform echoes the gray, empty band of wall in Approaching a City (1946, Phillips Collection, Washington, DC). Finally, the pattern of light on the pillar and platform recalls aspects of several quite different pictures, such as Hotel by a Railroad (1952, Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, Washington, DC) and New York Office (1962, Montgomery Museum of Fine Arts, Alabama). Despite its apparent darkness, Dawn in Pennsylvania radiates references, illuminating Hopper’s work as a consistent whole.