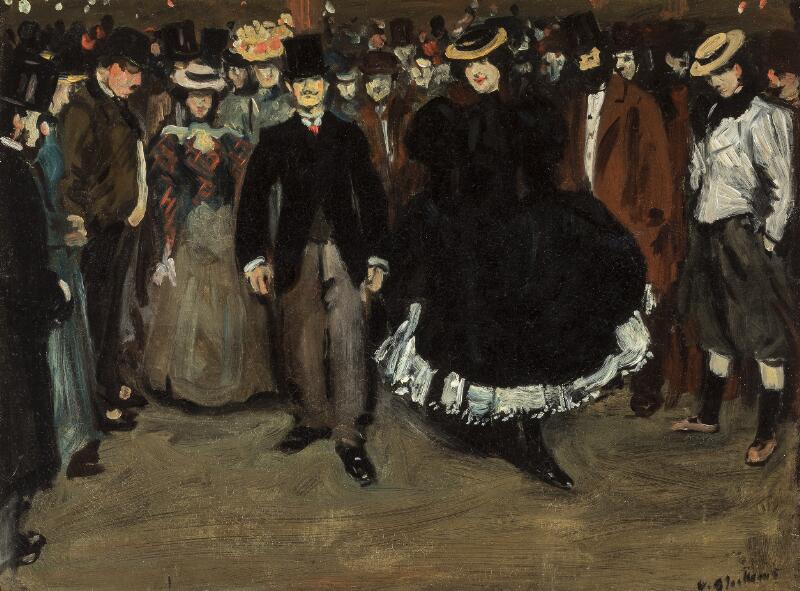

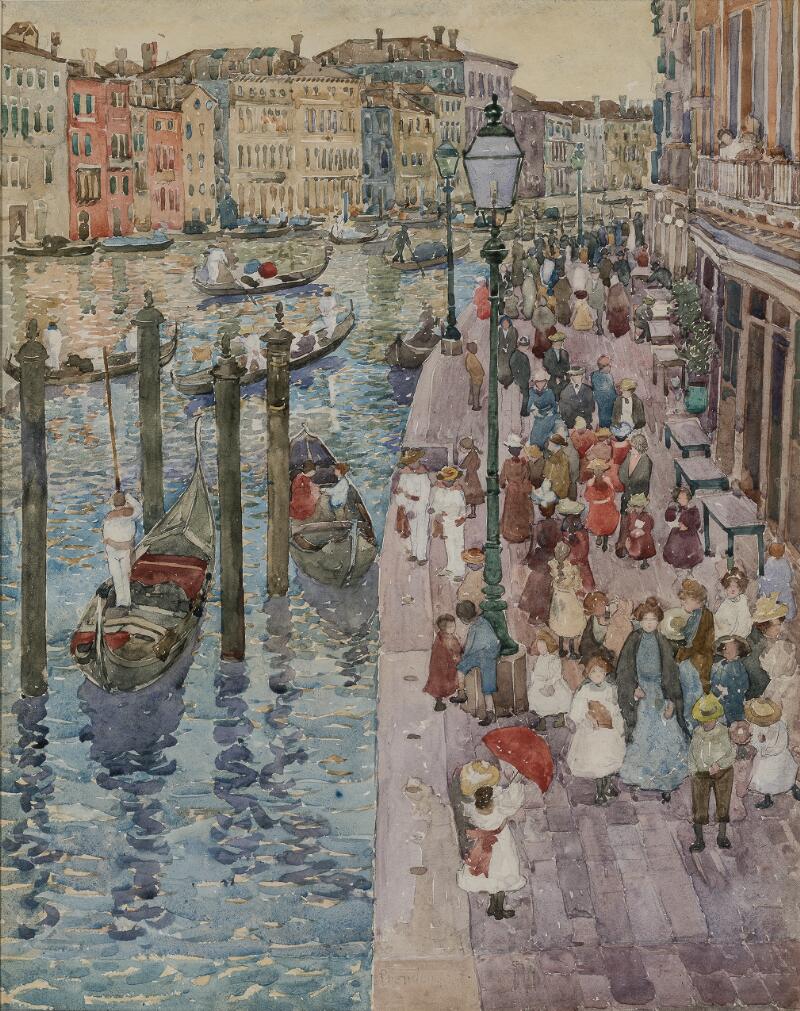

Here are two paintings, both made during the 1890s, both small in their dimensions, loosely or rapidly painted, and focused on urban everyday scenes: Street Corner in Paris (Fig. 1) by Robert Henri (1865–1929) and Evening on a Pleasure Boat (Fig. 2) by Maurice Prendergast (1858–1924).

Robert Henri (1865-1929)

Street Corner in Paris, 1896

Henri’s picture, which measures only 3 7/8 by 6 1/8 inches (9.8 × 15.6 cm), uses fluid but substantial paint to describe the rush and bustle of a city street. A figure in the foreground leans rightward as she strides toward a group of people, barely articulated, that occupy the middle ground. Behind this scatter of human presence, a canvas awning and solidly planted tree anchor the eye and buildings rear up, marking this as a city scene. The dominant impression, however, owes as much to the lushness and vitality of the brushwork as to the subject matter. The evident rapidity of the artist’s application of paint conveys the woman’s rolling gait, the ambulatory, vivid presence of the city’s inhabitants, and also their distance and anonymity. Henri’s figures possess the vagueness and indeterminacy of the stock figures art historians call staffage—groups or individuals that could be classified, recognized, or ignored in terms of “type,” rather than as discrete personalities. Henri’s small panel painting is a pochade—a swift, telling sketch—and derived from the example of the leading painter of nineteenth-century Parisian life, Édouard Manet (1832–1883). Its vision of the city is both pictorially seductive and indifferent to its human actors, a visual experience rather than a social one.

Maurice Brazil Prendergast (1858–1924)

Evening on a Pleasure Boat, 1895-97

Prendergast’s picture is slightly larger, at 14 3/8 by 22 1/8 inches (36.5 × 56.2 cm), and shows four well-dressed girls and one adult woman in a line, sitting against the railing of a boat as it steams through Boston Harbor. In an echoing frieze behind them, the cityscape of Boston passes in a regular rhythm, interrupted by the upright supports of the deck and by ships’ masts to the right and left. Prendergast’s rapid, generalized execution and summary description of the figures, along with the grid imposed by the rails, draw the fluency of the paintwork to our attention and reduce any sense of individuality. The girls appear as variations on a theme of decorous excitement set by their postures. The emphasis is on the scene’s typicality rather than on either the woman’s pleasure at the spectacle or the girls’ various negotiations of demureness. Though the city is visible behind them, they are distanced from it by the orientation of their seats and their prim attitudes. Evening on a Pleasure Boat is one of Prendergast’s earliest oils, painted at a time when he was mainly working in watercolor. The thin, expressive paint owes something to watercolor technique, and reinforces the sense of a consciously painterly work.

The emphasis in these paintings on the physicality and expressive immediacy of paint and its ability to seize urban experience evokes the work of the American expatriate James Abbott McNeill Whistler (1834–1903), whose canny balancing of representation and painterliness was powerfully influential in both the US and Europe during the final years of the nineteenth century.1 Henri’s Parisian pochade, with its assertive central awning, recalls the prints and small painted sketches of shop fronts such as Carlyle’s Sweetstuff Shop (c. 1887, Terra Foundation for American Art) that Whistler began making in the 1880s.2 Several of these employ horizontals and verticals in a grid effect similar to Prendergast’s lattice organization in Evening on a Pleasure Boat, while their rapid execution can be seen as a complement to the influence of Édouard Manet (1832–83) in Henri’s painting. Prendergast may also have been referencing Whistler’s images from the 1860s of the East London waterfront, a forest of masts and busy boats at the heart of a world city.

The painted sketches of Henri and Prendergast embody the tension, present throughout this period of American art, between aesthetic concerns—the designed, decorative, or explicitly painterly—and social ones, specifically the urban scene. The counterpoint between social description, with its rhetorical claims for authenticity, even grittiness, and aesthetic intent animates these images. Both artists offer views of human interaction in the modern city—Henri’s busy Parisians as much as Prendergast’s decorous observers—while foregrounding the artists’ expressive responses. In addition to this persistent dualism, these works raise the issue of how American painters represented modernity and responded to questions about the human experience of cities.

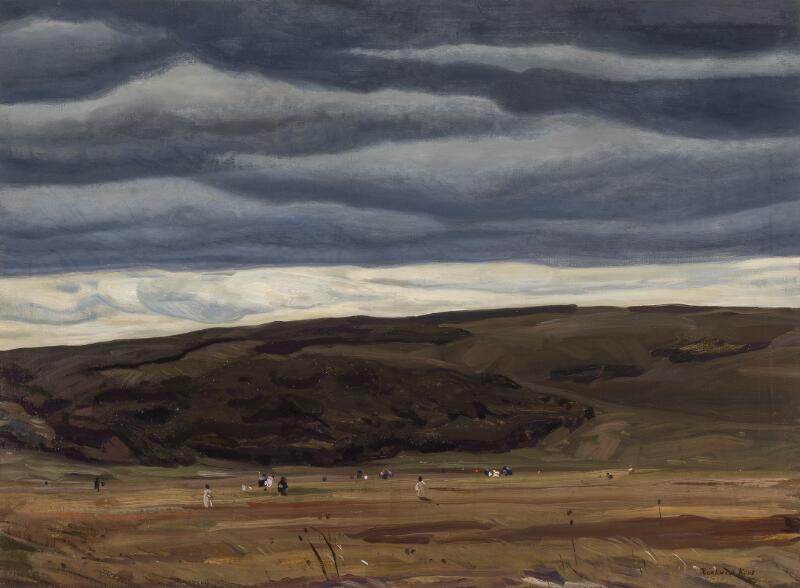

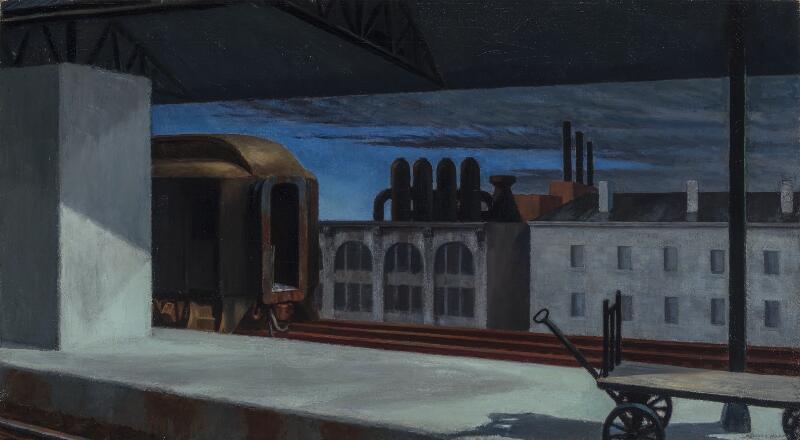

Painted about a dozen years later, The Palisades (Fig. 3) by George Bellows (1882–1925) and Brooklyn Bridge (Fig. 4) by Ernest Lawson (1873–1939) confirm a sense of the modern city as intense and demanding. Bellows’s Palisades depicts the view from Riverside Park in uptown Manhattan looking across the Hudson River to New Jersey. Between piles of snow in the foreground, a cleared path provides an opportunity for two walkers. Below the rolling snowbank on their right bare earth fades down to the river, marked on the near side by pylons, a pier, and a shed, and on the other by a cliff face of the Palisades. Between these two edges tugboats head down-river, while along the shoreline a train heading downtown belches a cloud of steam that fills the top right-hand corner of the canvas.

George Bellows (1882–1925)

The Palisades, 1909

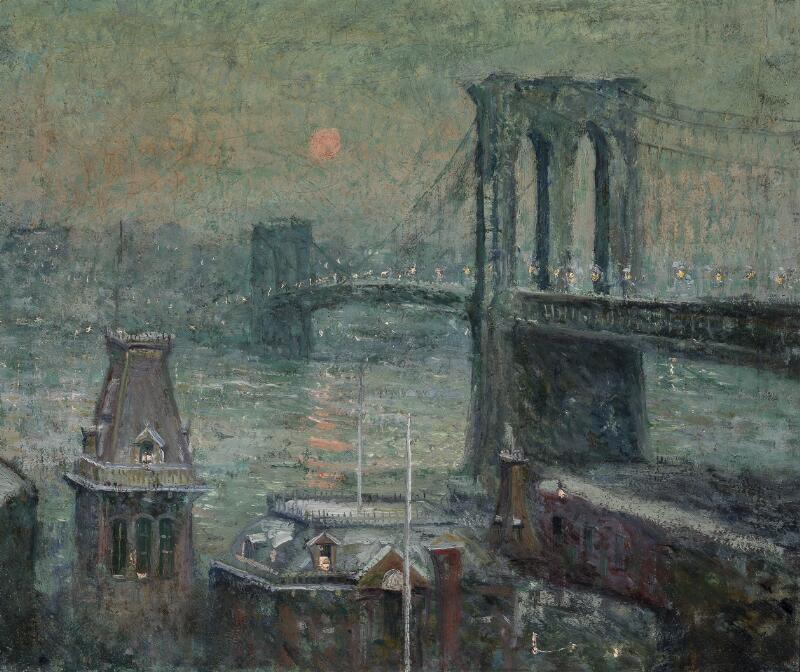

Ernest Lawson (1873–1939)

Brooklyn Bridge, 1917–20

Bellows was a prominent member of the Ashcan school, the group of painters (including John Sloan [1871–1951], Everett Shinn [1876–1953], and George Luks [1867–1933]) who followed Henri’s urging to paint the American scene, and his example in choosing to depict the New York of their daily lives. The Palisades is one of several paintings Bellows made around this time depicting the Hudson along Manhattan (then called the North River) and its adjacent cityscapes. Here he represents the strange modernity of a place where the city and the landscape meet and are transmuted. The river—a marker of the natural world—is brought within the urban sphere by the tugs, the strolling watchers, and the industrial structures at the water’s edge. At the same time, the park can be seen as the city’s attempt to reimagine itself as rural (though it achieves only an urban version of the natural world). The steam from the train merges almost indistinguishably with the white clouds and snow. The meshing of natural and artificial realms is asserted in this vaporous, condensed substance, which occupies so much of the canvas.

A further transformation occurs toward the top, where sharp splinters of trees and roiling billows of steam, immense in relation to the tiny train beneath them, abandon mimesis almost entirely and turn explicitly into paint. Bellows sets up a mobile series of substitutions, from steam to clouds to paint, which destabilizes the relationship between representation and the world it seeks to describe. Into this strange and unresolved environment Bellows inserts two strolling, top-hatted figures: positioned on a ridge, looking across at the yet untamed Palisades, these figures allow us to consider a different view—one that skips over the train and boats with their implications of a busy commercial world, taking in just the icy blue of the river and the black rock face above it. They see an aesthetic, rather than the dingy world of modernity.3

Instead of the urban-natural transition zone of Bellows, Lawson’s painting concentrates on the striking presence of the Brooklyn Bridge, a symbol of American progress completed in 1883. By the turn of the century, artistic expressions of the sublime—images evoking awe and mystery—had moved away from the wildernesses that had inspired nineteenth-century American painters and had begun to seek out the soaring buildings and complex infrastructure of the twentieth-century city. As this technological sublime became a prime mode of representing American modernity, the marvel that was the Brooklyn Bridge emerged as one of its principle subjects. It was ceaselessly represented and written about in popular and official culture in the decades after it opened.4 But Lawson’s painting contains another, perhaps surprising, element: painted from the Brooklyn side, looking toward Manhattan, it depicts in the foreground a cluster of buildings from the 1860s, including the Fulton Ferry Terminal—an instance of the supersession of one defining technology by another.5 The Fulton Ferry had been the first public steamboat service between Brooklyn and Manhattan in the early nineteenth century, and had been critical to the development of Brooklyn Heights as a commuting community.6 Hard hit by the opening of the bridge, the ferry and its old-fashioned terminal suggested the rapidity of change when Lawson painted his scene.

In this sense, the picture seems less a vision of technological sublimity than of the melancholy traces of a vanishing past. Lawson and Bellows both seem somewhat disenchanted with the industrialized American city of their time. The sulfurous atmosphere and lowering sun of the Lawson, like the dark blues and disintegrating wooden structures of the Bellows, seem to reflect a world of rapid change and decay. Human beings are peripheral to these urban spaces. The protagonists of these paintings are the rivers, and the mechanical systems that gather around them. Manhattan’s rivers are part of the story of its growth and development, but they are also separate from it.

A quite different vision of New York can be found in two paintings of the 1930s: Pip and Flip (Fig. 5) by Reginald Marsh (1898–1954) and Coney Island (Fig. 6) by Harry Roseland (1867–1950). Both expand on the theme of waterfront pleasures that had been explored in earlier Ashcan painting, including Bellows’s Beach at Coney Island (1908, private collection) and Sloan’s South Beach Bathers (1907–08, Walker Art Center, Minneapolis, Minnesota). The somberness of Lawson’s Brooklyn Bridge and Bellows’s Palisades is absent here; people move to center stage, explored as masses and as objectified subjects.

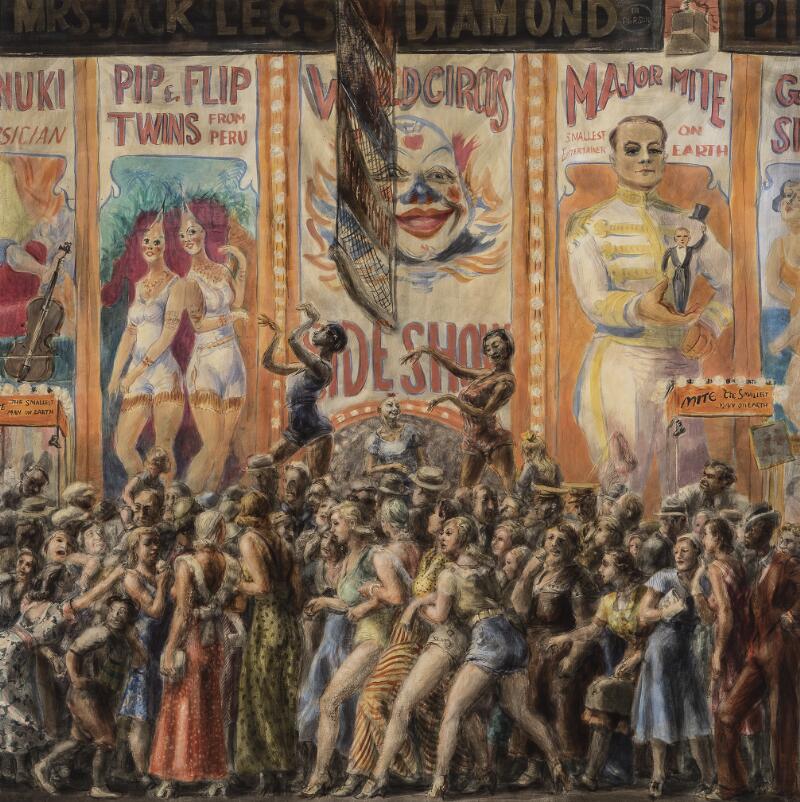

Reginald Marsh (1898–1954)

Pip and Flip, 1932

Harry Roseland (1866–1950)

Coney Island, 1933

Roseland’s Coney Island bears comparison with the Coney Island pictures taken in the 1940s by the documentary photographer Weegee (Arthur Fellig, 1899–1968), such as Coney Island Beach (Fig. 7). Weegee, like Roseland, emphasized people en masse, fluctuating, fractal, and infinitely mobile. He captured individuals within the crowd who looked up as the photographer, famously, mugged and danced to attract their attention. The people in Roseland’s crowd, however, turn away from the painter (and viewer), pursuing their own activities and blending into an anonymous, immeasurable mass.

Weegee (Arthur Fellig) (1899-1968)

Coney Island Beach, 1940

Gelatin silver print, 8 1/8 x 10 in. (20.6 x 25.4 cm), The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Ford Motor Company Collection, gift of Ford Motor Company and John C. Waddell, 1987.1100.252

Marsh focused on the culture of popular entertainment, leisure, and exploitation. In Pip and Flip, a river of humanity passes from right to left across the composition, a flow of social, racial, and gender types that ebbs toward the picture’s edges and crests before the entrance to World Circus, a famous Coney Island “freak show.”7 Above them, brash signs for the acts inside dominate the canvas through egregious scale and color. In the center, where two burlesque performers and one of the headliners stand above the crowd, a huge clown face is capped by a word play where a hanging flag transforms “World Circus” into “Wild Circus.”

“Pip” and “Flip” were the stage names of the microcephalic sisters Elvira and Jenny Snow, who also appeared in the movie Freaks, directed by Tod Browning and released the same year. Robin Jaffee Frank has written about Marsh’s painting and the realities of Coney Island and its entertainers, stressing Marsh’s emphasis on sexuality and the coarser human emotions.8 The sodality of linked girls who stride across the midpoint of the painting, the burlesque dancers who pose to attract the crowd, the interplay of types and glances—all contribute to a vision of the city quite distinct from the empty built spaces of Lawson’s Brooklyn Bridge or the emotional distance of Bellows’s Riverside Park. Coney Island represented a different American modernity.

Up to now, all the pictures I have discussed have been of urban locations—Paris and Boston, and New York City from Riverside Park to Coney Island. The last two paintings I will discuss, however, use modernist stylistic devices to represent rural environments: in Bucks County Barn (Fig. 8) by the precisionist painter Charles Sheeler (1883–1965), the material structures of human endeavor stand without their makers, while After Church (Fig. 9) by Romare Bearden (1911–1988) is jammed with human presence, as palpable and obdurate as buildings.

Charles Sheeler (1883–1965)

Bucks County Barn, 1940

In the early years of the twentieth century, Sheeler had depicted New York City in paintings, works on paper, and photographs, but at the same time he repeatedly portrayed the landscape and architecture of Bucks County, Pennsylvania, where he shared a colonial house in Doylestown with his friend the painter Morton Schamberg (1881–1918) until the latter’s death from influenza in 1918. Sheeler’s Bucks County Barn exhibits the tension between realism and self-conscious aestheticism we saw in Henri and Prendergast. Sheeler’s first sustained artistic encounter with vernacular architecture occurred in the late 1910s, when he produced a large number of photographs and works on paper depicting the interior of his Doylestown house and nearby buildings.9 By the 1930s, rural and historic subject matter of this sort, which had been seen as eccentric and innovative when he began, had become a more common modernist interest, and Sheeler’s impersonal, precisionist technique had become identified with the depiction of industrial and urban sites. His formal geometries and evocation of historical America through vernacular structures suggested to critics and contemporaries a specifically American modernism.10

Bucks County Barn, like Lawson’s Brooklyn Bridge, is unpeopled. The only living things are two cows behind a split-rail fence and a dog passing by a kennel, which divides his body. Human presence is implicit in the architecture and tools—means of structuring the world. Mortality and the dissolution of the body are evoked by the collapsed fence and a damaged board on the porch roof.

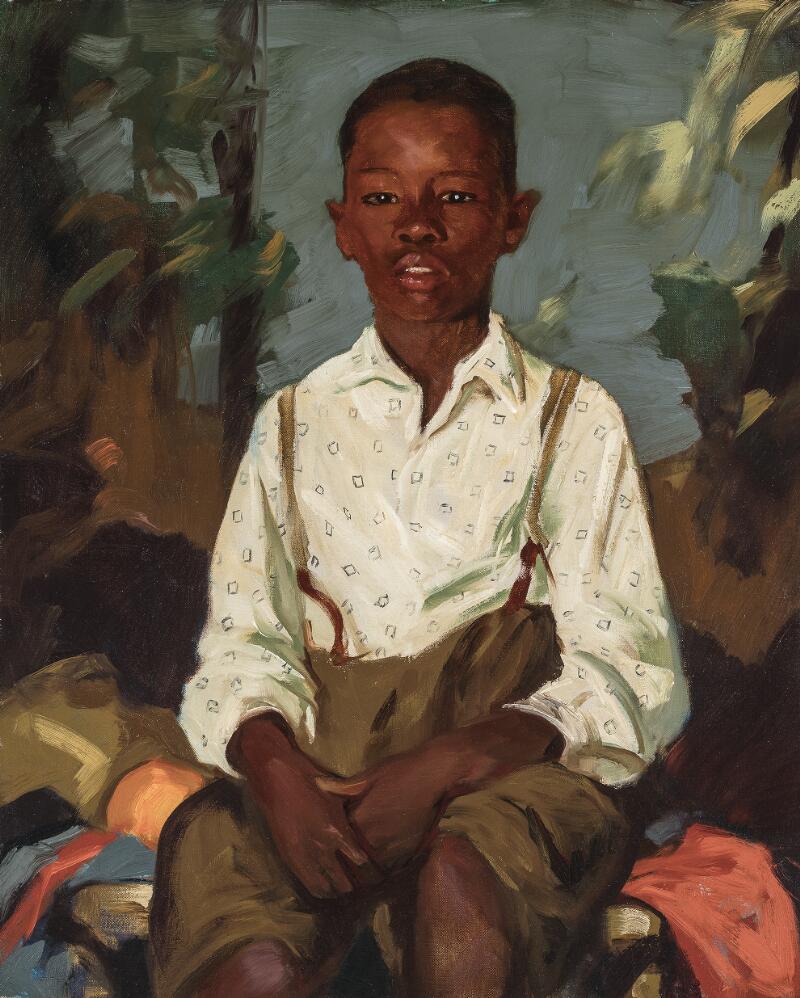

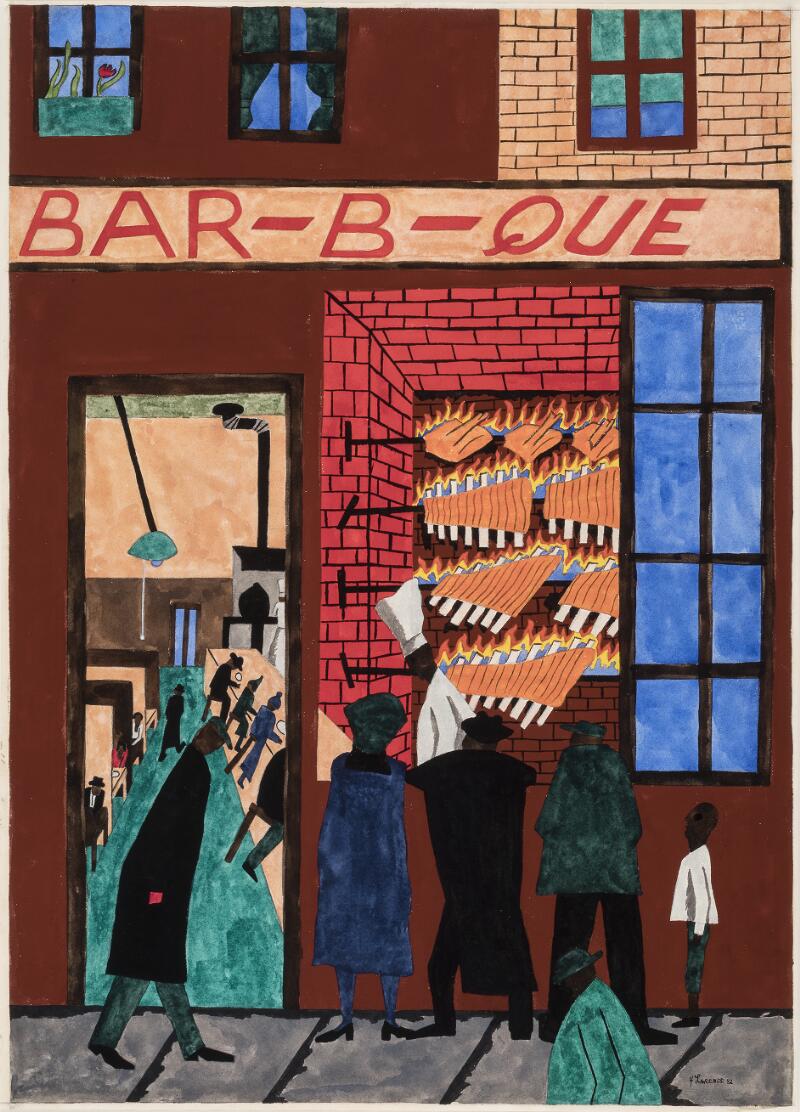

Romare Bearden (1911–1988)

After Church, 1941

Bearden, a generation younger than Sheeler, adapted the formal simplifications and spatial contradictions of modernism to a subject it had rarely been tasked with: African American life in the twentieth century. Born in the southern state of North Carolina, Bearden moved with his family to New York as a young child. After Church is one of several works that emerged from a return visit to the South he made in the early 1940s. On the face of things, the subject is a brief and unremarkable moment as men leave a country church after a service, but the mood is silent and ominous. The composition is dominated by the heads and shoulders of large figures who push up against the picture plane, while in the distance rolling hills and leafless trees frame two smaller figures and the gray clapboard church.

Bearden’s subtle understanding of historical and contemporary painting is evident in the Matisse-like flattening of form and brilliant colors. The men appear near to us and therefore implicitly require a response, but this immediacy is subordinated by the formal choices Bearden makes and by the closure of feeling in the figures’ faces, deportment, and address to the spectator. One is seen in profile, his eyes hidden by the brim of his hat; the frontmost raises a handkerchief to his face and glances off to the side; a third, wearing a cloth cap and smaller than the others, stands apart and faces us squarely, but his eyes are lowered and do not meet the viewer’s. The faces of the figures behind cannot be seen at all. Everyone and everything appears simultaneously direct and evasive. This depiction of the Jim Crow South, seen from the perspective of a New York painter, is a further example of an American artist consciously maneuvering between pictorial strategies, personal vision, and social subjects.

Bearden’s painting returns us to the concerns with which this essay opened: the decorative and aesthetic, the socially meaningful, the desire to characterize the present moment, and the questioning of American identity and its symbols. If much of this activity concentrated on the nation’s greatest metropolis—its most dizzying exemplar of mankind’s technological interventions in the natural world—it also looked further afield, to the “old world” of Paris and to the deep American time of Boston Harbor, Pennsylvania farm country, and the former Confederacy.

-

Linda Merrill, After Whistler: The Artist and His Influence on American Painting (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2003) ↩︎

-

In addition to Carlyle’s Sweetstuff Shop (c. 1887), Whistler is represented in the Terra Foundation’s collection with A Brittany Shop with Shuttered Windows (c. 1893), A Chelsea Shop (1894–95), and Flower Shop, Dieppe (1897 or 1899). ↩︎

-

This connects to Bellows’s many paintings of snow scenes in the city, such as Blue Snow, the Battery, 1910, Columbus Museum of Art, which won him popularity during his lifetime. ↩︎

-

Richard Haw, The Brooklyn Bridge: A Cultural History (New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 2005); and Sarah Kate Gillespie et al., Icon of Modernism: Representing the Brooklyn Bridge, 1883–1950 (Athens, GA: Georgia Museum of Art, University of Georgia, 2016). ↩︎

-

“Interpretation”, Ernest Lawson, Brooklyn Bridge, 1917-20. ↩︎

-

William R. Everdell, Rowboats to Rapid Transit: A History of Brooklyn Heights (Brooklyn, NY: Brooklyn Heights Association, 1973). ↩︎

-

On this compositional device in Marsh’s paintings, including Pip and Flip, see Carmenita Higginbotham, “At the Savoy: Reginald Marsh and the Art of Slumming,” Bulletin of the Detroit Institute of Arts, vol. 82, no. 1/2 (2008): 16–29. ↩︎

-

Robin Jaffee Frank, Coney Island: Visions of An American Dreamland, 1861–2008 (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2008), especially 96–99. ↩︎

-

Karen Lucic, Charles Sheeler in Doylestown: American Modernism and the Pennsylvania Tradition (Allentown, PA: Allentown Art Museum, 1997) and Karen Lucic, “The Present and the Past in the Work of Charles Sheeler” 2 vols. (PhD diss., Yale University, 1989). ↩︎

-

Wanda Corn, “Home, Sweet Home,” chap. 6 in The Great American Thing: Modern Art and National Identity, 1915–1935 (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1999). ↩︎